(Photo: Michael Yalamas)

WRITTEN BY MARINA GOMBERG

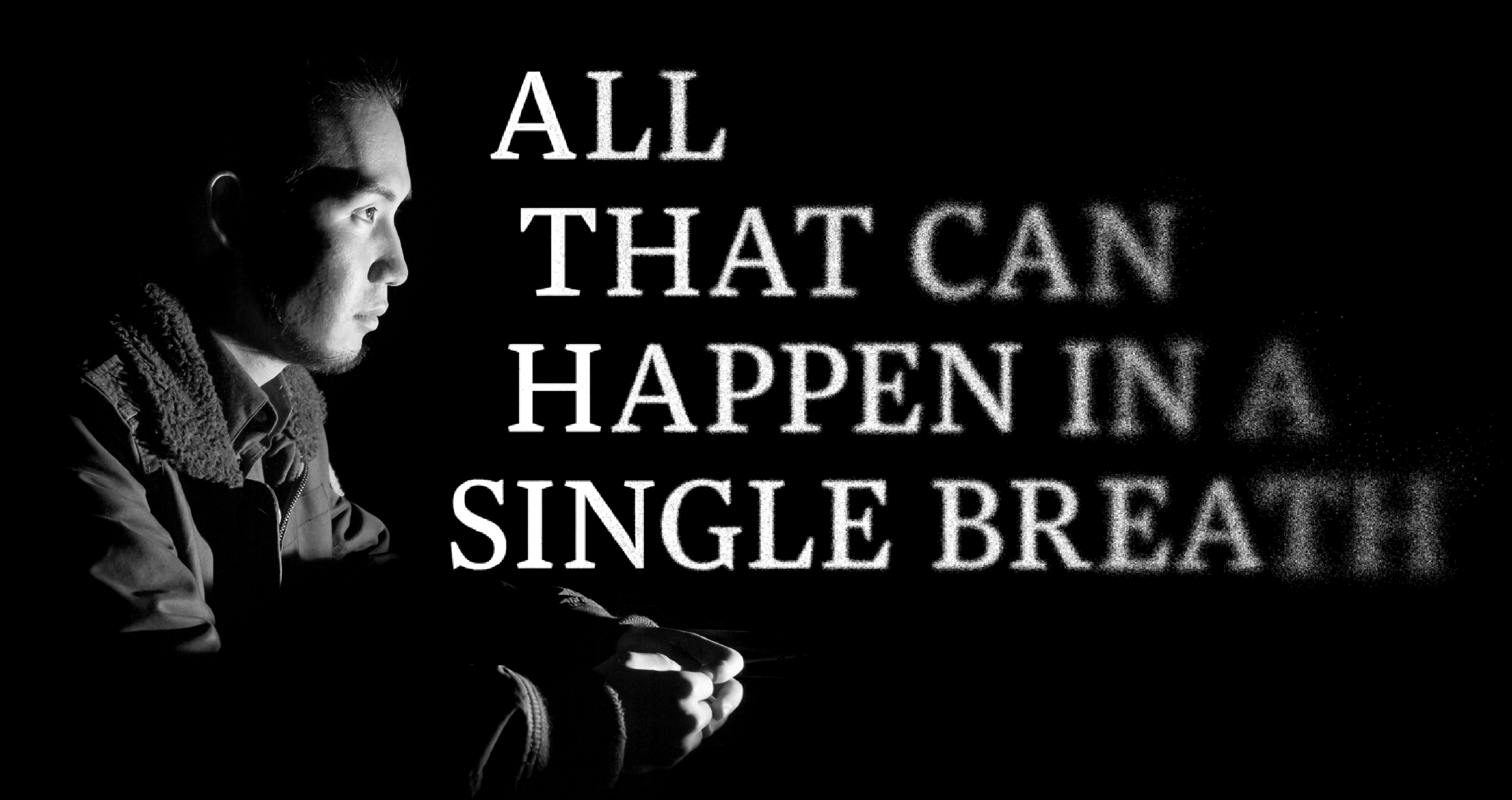

Viewing artist Kei Ito’s work is a breathtaking experience in and of itself. The imagery is striking and provoking just in its aesthetic. It’s like it radiates its own heat. It’s haunting. And when you come to understand his inspirations for and processes of creating the works, the influence deepens immeasurably.

He literally puts himself in each of his works, which he often makes through a camera-less photography practice which exposes the sun to light-sensitive paper to the rhythm of his breath.

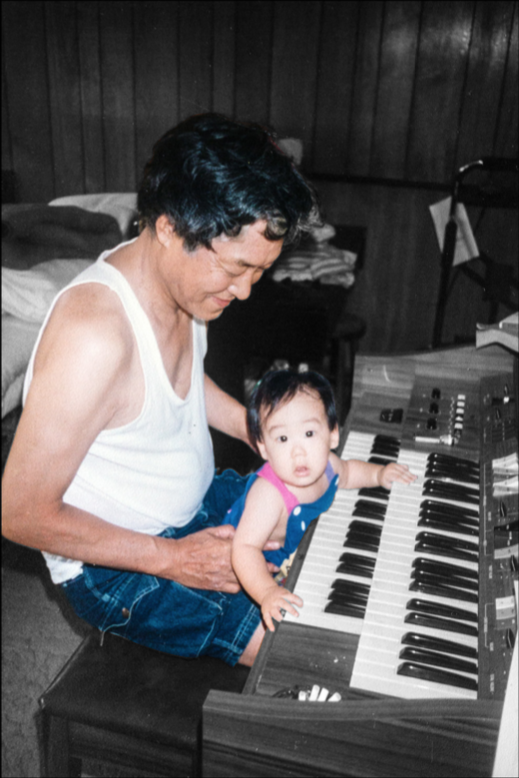

Ito is a rising conceptual artist and the Spring 2020 Marva and John Warnock Artist in Residence for the University of Utah Department of Art & Art History. His work with students through his class, “The Art of Trauma,” shares the powerful and healing practice of making work that confronts past trauma.

(Photo courtesy of Kei Ito)

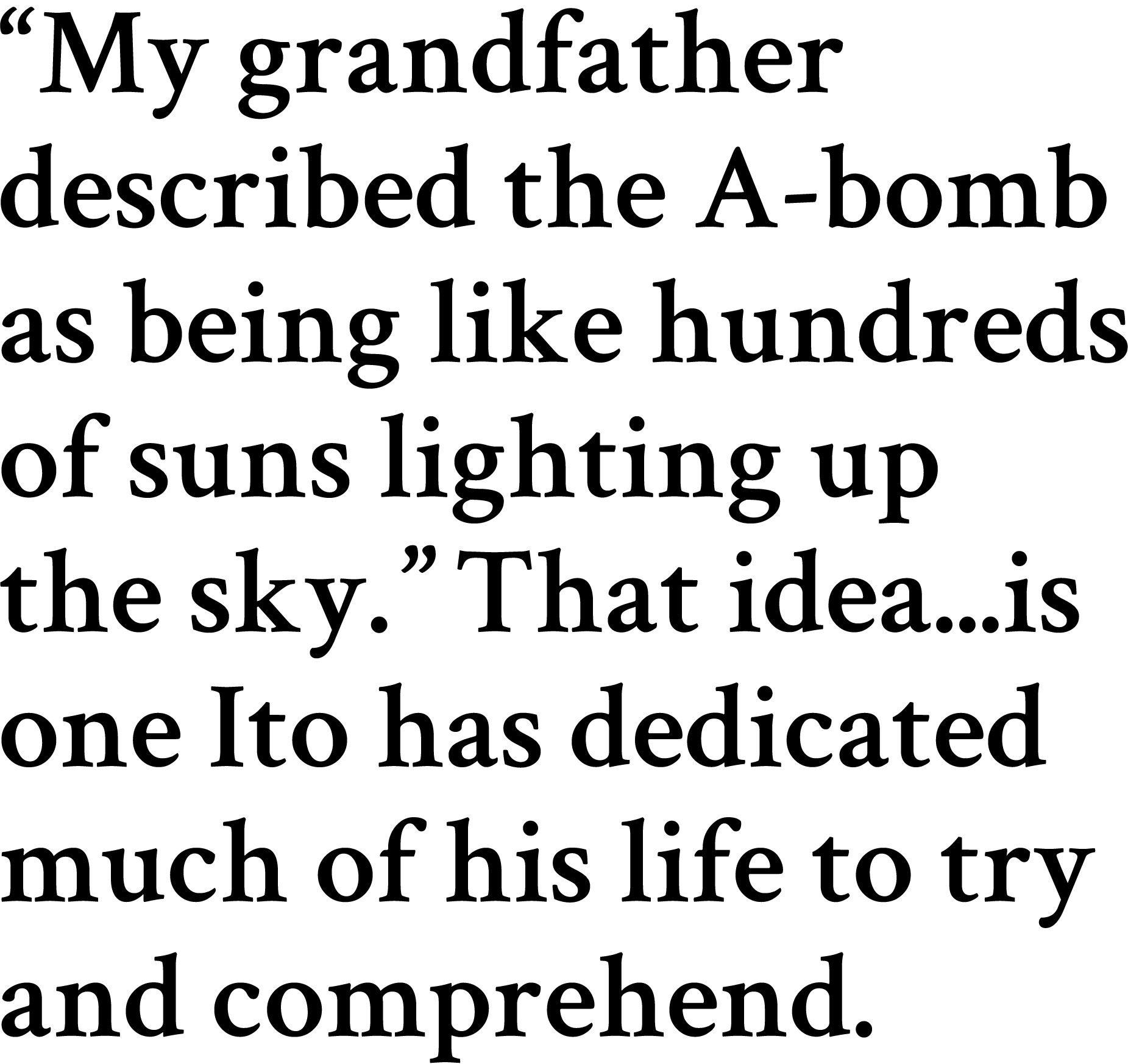

Keo's grandfather, Takeshi Ito, holds baby Kei Ito at the piano. (Photo: Jun Ito)

Kei Ito class poster.

“Everyone has some sort of trauma,” he says. “It doesn’t matter how big it is or how cultural it is. It could be personal. It could be collective. But everyone has trauma that makes them want to change the world.”

His is exploring the devastation of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima during World War II. A familial trauma. A generational trauma.

Ito wishes he remembered more or had asked more questions of his grandfather who witnessed and survived the bombing, but who died of cancer when Ito was nine years old. What he does remember, though, has inspired his work, which has catapulted him into national renown.

“My grandfather described the A-bomb as being like hundreds of suns lighting up the sky.”

That idea — the brightness, the heat, the destruction — is one Ito has dedicated much of his life to try and comprehend. And it was during his MFA at the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) that he came into an art practice that has helped him heal.

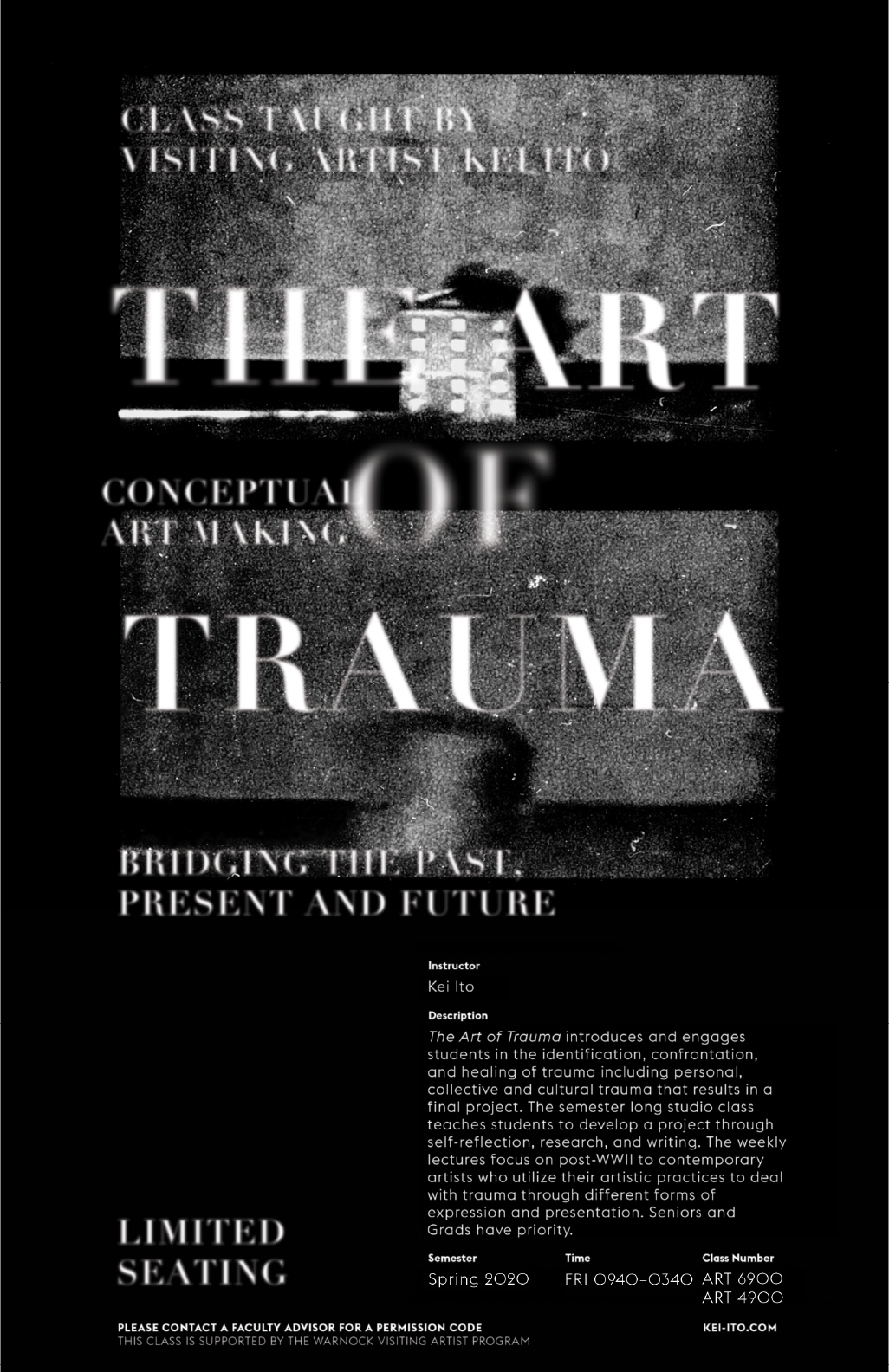

View of “Sungazing Prints” at the exhibition at Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art, NC. (Photo: Kei Ito)

Ito’s signature piece, which he conceptualized during that time, called “Sungazing” is a collection of 108 letter-sized prints, each a blinding representation of what can be materialized in just a single breath.

“’The Art of Trauma’ is not just about victimhood, though” Ito says. “It’s a reclamation. A redemption. It’s about understanding. It’s a process of healing through which sometimes the artwork is just a byproduct.”

Which is why there 108 pieces in the collection. Because in Japanese Buddhist tradition, between New Year’s Eve and New Year, Japanese temples ring human-size bells once for each of the believed 108 evil human desires. It is a cleansing ritual said to rid the body of evil before the new year.

“Sungazing” was the beginning of Ito’s redemption, and it’s a work he recreates annually with various modifications. Some iterations are 200-foot scrolls marked by the sunlight of 108 of Ito’s breaths on a roll of light-sensitive paper, one of which was collected by The Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago and another by The Norton Museum of Art in Florida.

“Photography is such a set or fixed media. And so often we think that a photograph needs to be framed and displayed on a wall in order to be taken seriously. But I always thought that photography can be something more than that. I wanted to create photographic art that pushes the boundary of the idea of what photography is.”

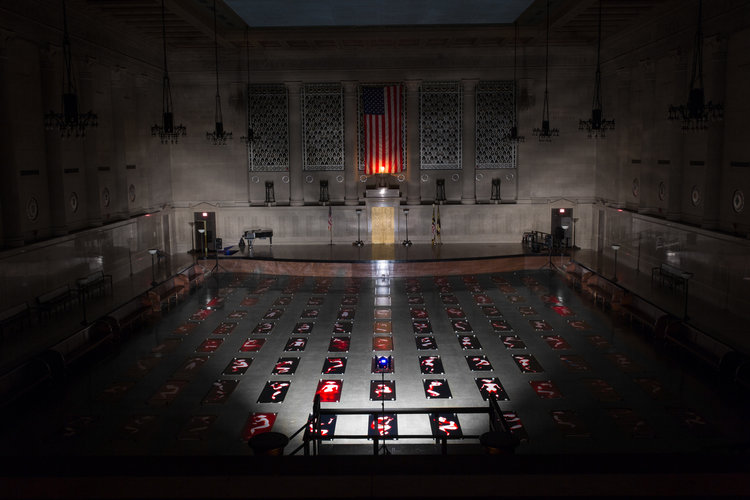

Kei Ito and curator, Liz Faust, installing Afterimage Requiem at the Baltimore War Memorial, MD. (Photo: Michael Yalamas)

So, now picture 108 human-scale photograms made by the shadows of his own body. The feeling of burned flesh and human tragedy effervesces from each one and the collection all together is unforgettable.

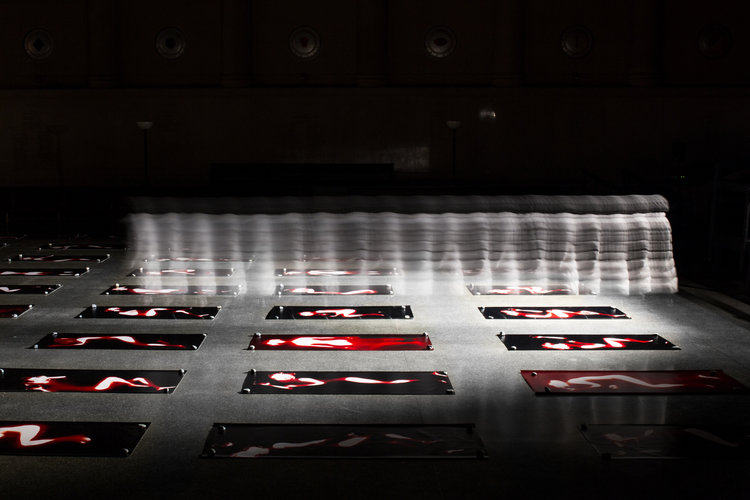

“Afterimage Requiem” is a massive visual and sound installation made with Ito’s sound artist collaborator, Andrew Keiper, Ito’s colleague and former housemate during graduate school at MICA.

The two vowed to make work together one late night when they realized the connection of their family histories: Keiper’s grandfather was an engineer who helped develop the atomic bomb during the Manhattan Project.

Collaboration. Reconciliation. Healing.

Afterimage Requiem (Photo: Michael Yalamas)

Afterimage Requiem (Photo: Michael Yalamas)

Afterimage Requiem (Photo courtesy of Kei Ito)

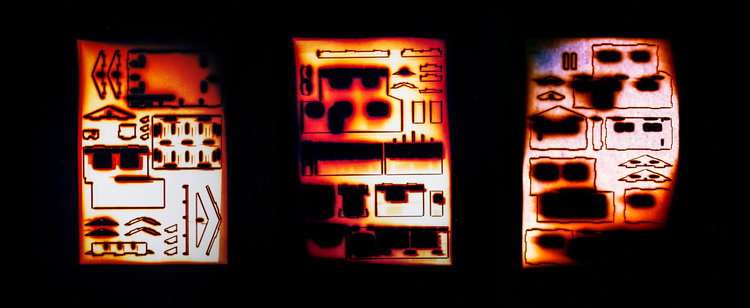

And Ito doesn’t just create art about the passed-down intergenerational trauma. Like so many others, he has traumas of his own to inform new work, like “Infertile American Dream” which is a triptych of C-prints depicting a disassembled model house created by exposing light-sensitive paper to sunlight on the day the 45th U.S. president was elected to office.

“When Trump was announced to be the president, I felt this sense of denial from this country where I have been working so hard to become a member of,” he recalled. “America has always been touted as a place for a fresh start and providing a chance to build one’s home. However, after the election it felt as if the American Dream could no longer even be conceived.”

Infertile American Dream (Photo courtesy of Kei Ito)

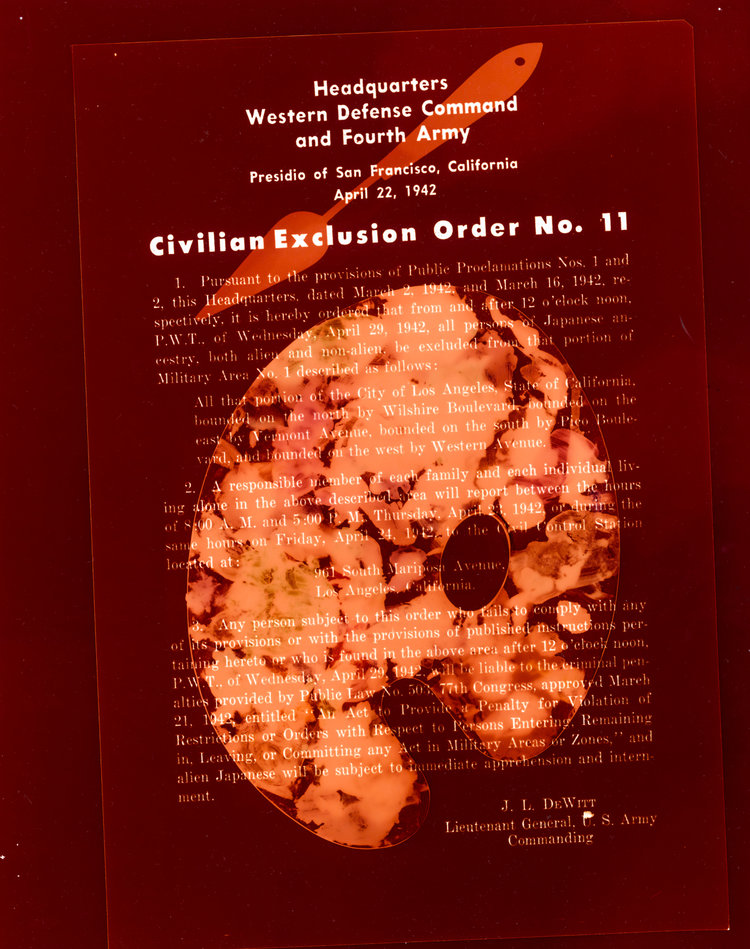

Civilian Exclusion Order No.11 : Paint Pallet and Paint Knife - Only What We Can Carry (Photo courtesy of Kei Ito)

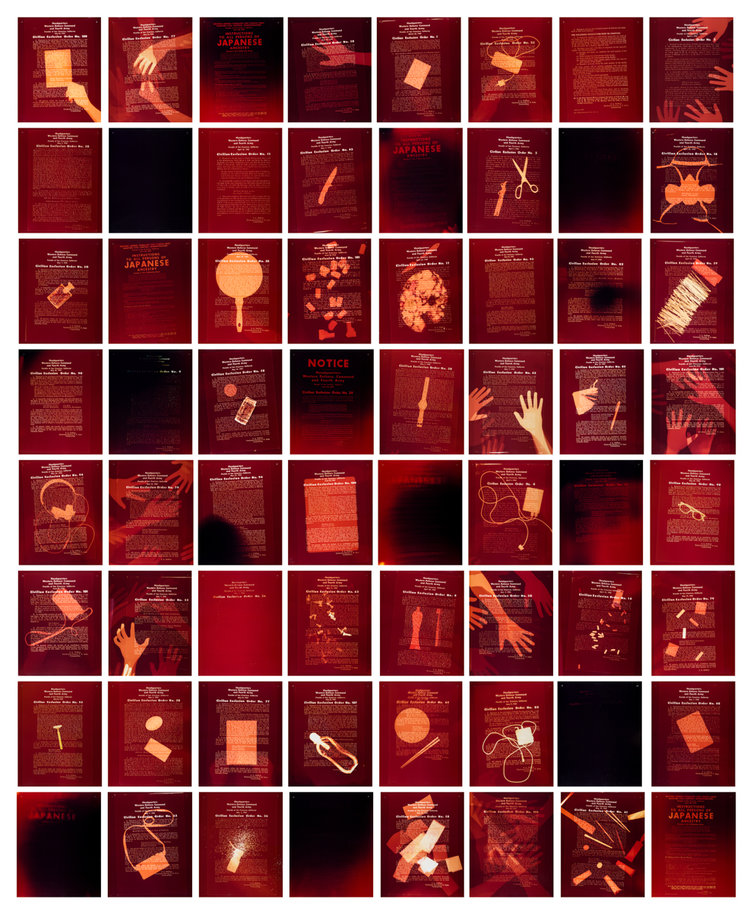

Only What We Can Carry (Photo courtesy of Kei Ito)

His work has reflected on American politics and drawn arresting connections like that of the Japanese internment camps and the Muslim travel ban in his work “Only What We Can Carry.” He has also pursued narratives around other nuclear crises like Fukushima in “Ravaged Flower of the Future.”

And all with camera-less image-making.

“When you think about photography, you think about using a camera which is a lens-based media. The lens pointing outward captures what’s in front of you. However, if you want to capture something that’s already gone, invisible, or exists only in memory — how do you capture these phenomena? My answer to that was to abandon the camera. Get rid of it entirely and use the most conceptual base of photography: light sensitivity.”

He says, now that “everything has been done aesthetically, the only way you can create something new – something interesting – is by adding who you are in the artwork.” ■

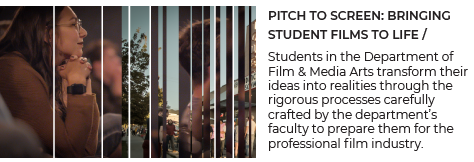

Marva and John Warnock Artist in Residence

The Marva and John Warnock biennial residency program, which began in 2010, has quickly become an important catalyst for dialogue encompassing contemporary issues of art making, pedagogy, interdisciplinary and collaborative work, art in the community and art as activism. The program aims to expose students to new, innovative, and diverse contemporary art practices, while providing an opportunity for trilateral exchange amongst students, faculty, and the public at large. The artist-in-residence will lead a Master Class that takes the form of intensive workshops throughout the semester.

“Art has always had the power to unite and heal. In today’s political climate, we have become even more aware of our differences and see cultural diversity and the give and take of different perspectives and innovations as a strength. Kei’s art carries forward the work of his grandfather by bringing awareness to the threat of nuclear war in a profound way, which opens up space for dialogue and hopefully social change. We believe that bringing Kei to Utah to teach this class provides our students a great opportunity to understand how art is changing laws, policies, relations, and perspectives.”— Henry Becker, Assistant Professor, Art & Art History