WRITTEN BY MARINA GOMBERG

Unprecedented Times

March of the year 2020 charged in like a lion. A lion with a contagious and deadly virus on its back.

The chaos started with the global pandemic and stay-at-home orders. It was punctuated by earthquakes. And was compounded by social injustice and unrest, a devastating windstorm, political tensions, and a deadly insurrection.

The earth literally shook under our feet and the sky seemed to fall. But even over a year later, we're only barely seeing any signs of that lamb. And nearly nothing is the way it was before.

Except, like always, artists persist.

Henry Becker, seen from above, teaching in his modern at-home set up.

(Photo courtesy of Henry Becker)

Accelerating Institutional Evolution

Assistant Professor of Graphic Design in the Department of Art & Art History, Henry Becker, remembers how abruptly we all had to transition from our traditional modes of teaching and learning to new ones shortly after the first COVID-19 cases showed up on campus. It necessitated an immediate evaluation of what and how he had been teaching.

Pre-pandemic, the bulk of education in the U’s graphic design program, like most other disciplines, had taken place in the classroom. Teaching in person, practicing in person, collaborating in person. Everything was in person.

Until it couldn’t be.

“It was challenging, and it presented many problems,” he said. “But I also see it as a necessary wakeup call for institutions of higher education to adjust to our current times.”

Fortunately for Becker (and his students), his personal and professional work had illuminated how much of the graphic design industry was already functioning successfully online. Unlike some professors, Becker didn’t have to necessarily learn new software in order to teach, he just had to introduce new software in order to help students learn the skills of the modern workforce.

Online design software like Miro and Figma have existed for some time, and allow for real-time collaboration from anywhere in the world. It’s not just important to understand the mechanisms of the software, but how to engage in creative processes with others when you can’t be or aren’t in person.

“As I tell my students, ‘The principles of design are constant, but the technology always will change,’” Becker said. “To really prepare our students for the way design is being done today, we have to ensure they can function successfully in remote environments.”

Another value of the software is that it allows Becker to digitally replicate the time in class when he’d normally be walking around while students are working to ask and answer questions, give guidance, and problem-solve together.

“I chose to keep that live during-class working time even in the online environment. It allows me to still visit their spaces and provide the same real-time support I’ve found to be so helpful in the classroom.”

But even when he can safely convene students in person again, Becker says these pandemic learnings have catapulted his teaching into the future.

“It’s odd but fair to say that the pandemic has sped up the evolution of our university.” ■

A Few Beats Ahead

The School of Dance has a long and vibrant screendance history, which Benjamin Sandberg, Assistant Professor and Audio-Visual Specialist, says is partly what made the school’s overhaul from typical stage performances to live-streamed broadcasts so successful.

“We were ahead of the curve in a lot of ways,” he said. “Because of screendance, my position as an A/V specialist had existed for some time and we have state-of-the-art video equipment that we know how to use specifically for dance.”

For years, Sandberg has worked alongside Assistant Professors Cole Adams and Isaac Taylor to film all performances with a two-camera set-up, one stationary and one moving.

“Fortunately, we had a pretty big infrastructure already in place,” said Adams who is also the school’s Production Director and Lighting Design. “With two broadcast-quality cameras, switchers for many feeds, and the IT know-how to film our shows and broadcast them live (thanks to Ben).”

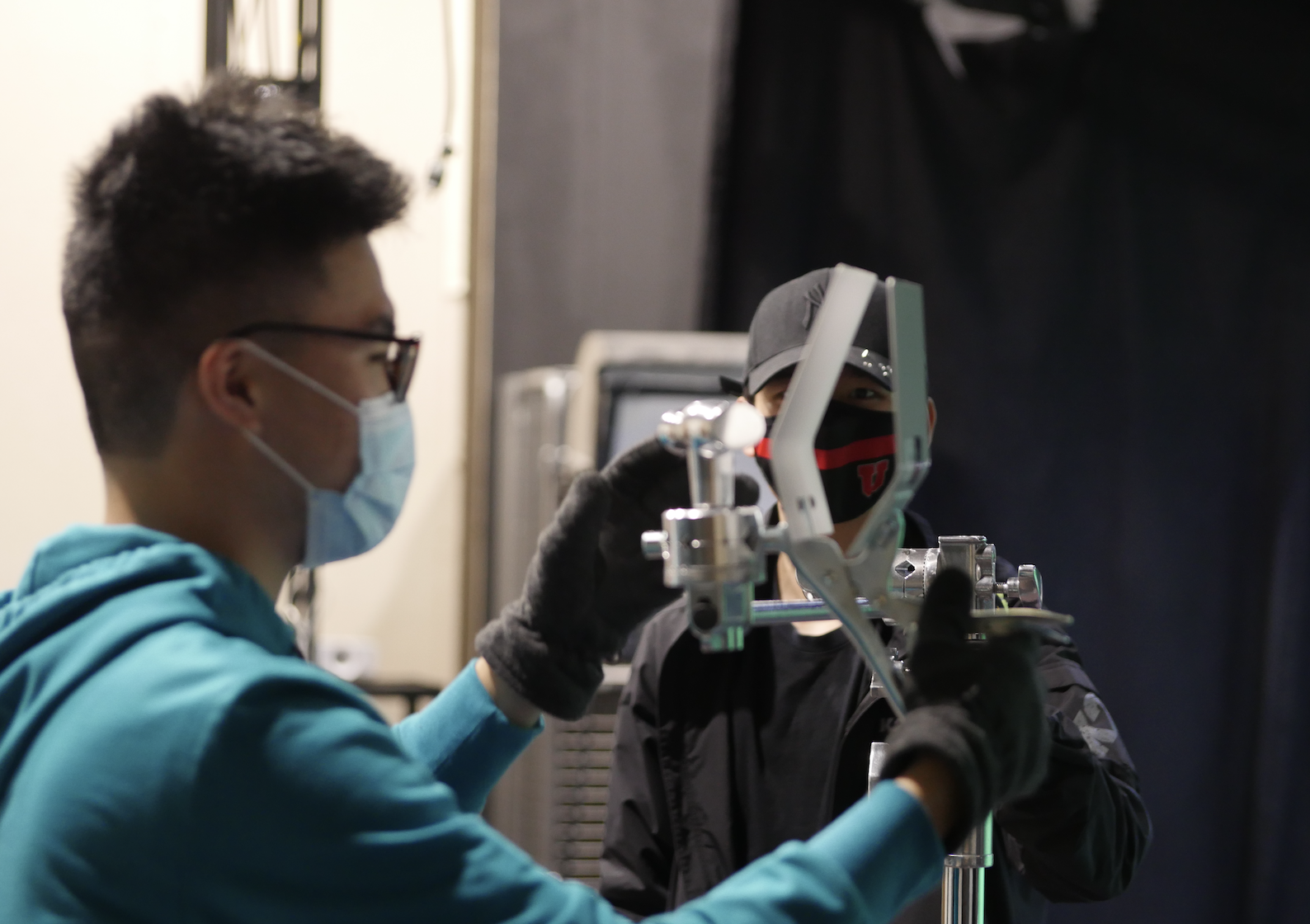

With a few additional pieces of equipment, lots of cable, considerable time working on angles and creative and safety strategies, the team — which includes Stage Manager Rebecca Johnson and an incredible custodial staff — were finding their groove.

Of course, to have dancers actually in the space, even masked and distanced, required new stringent guidelines and practices. The students were split into pods to reduce the number of people in any space, and classes and rehearsals were streamed live throughout the building and to their homes while they’d collaborate and learn.

The floors were adorned with new outlines for physical distancing, the building was equipped with new sanitation stations, and Taylor, who is also the Technical and Lighting Designer, noted that “the faculty made space for student entrances and exits to be staggered. We also bought commercial air purifiers that recycle the air every 30 min.”

The learning and making of work processes were ready. Next up were the logistics of sharing the work with the world. Adams and others worked with award-winning Communications Specialist Molly Powers to create a new section of the school’s website for live-streaming, and they made the tough but important call to make all performances free to the public. A note on the website read,

School of Dance student crew members working a show. (Photo: Benjamin Sandberg)

“We recognize that the arts are a vital part of our connection to one another, and we need connection now more than ever. So, we, in the School of Dance, have made the decision to provide free access to any patron who would like to be moved by our movement this year. No cost. Just click.”

And people did.

With some of their largest audiences ever, and certainly the most geographically diverse, these virtual shows may become part of the new standard.

“Having the shows available for our students’ families and friends around the world is very exciting,” Adams said. “It allows for them, and potential students, to be connected to the students’ experience at the University of Utah School of Dance.” ■

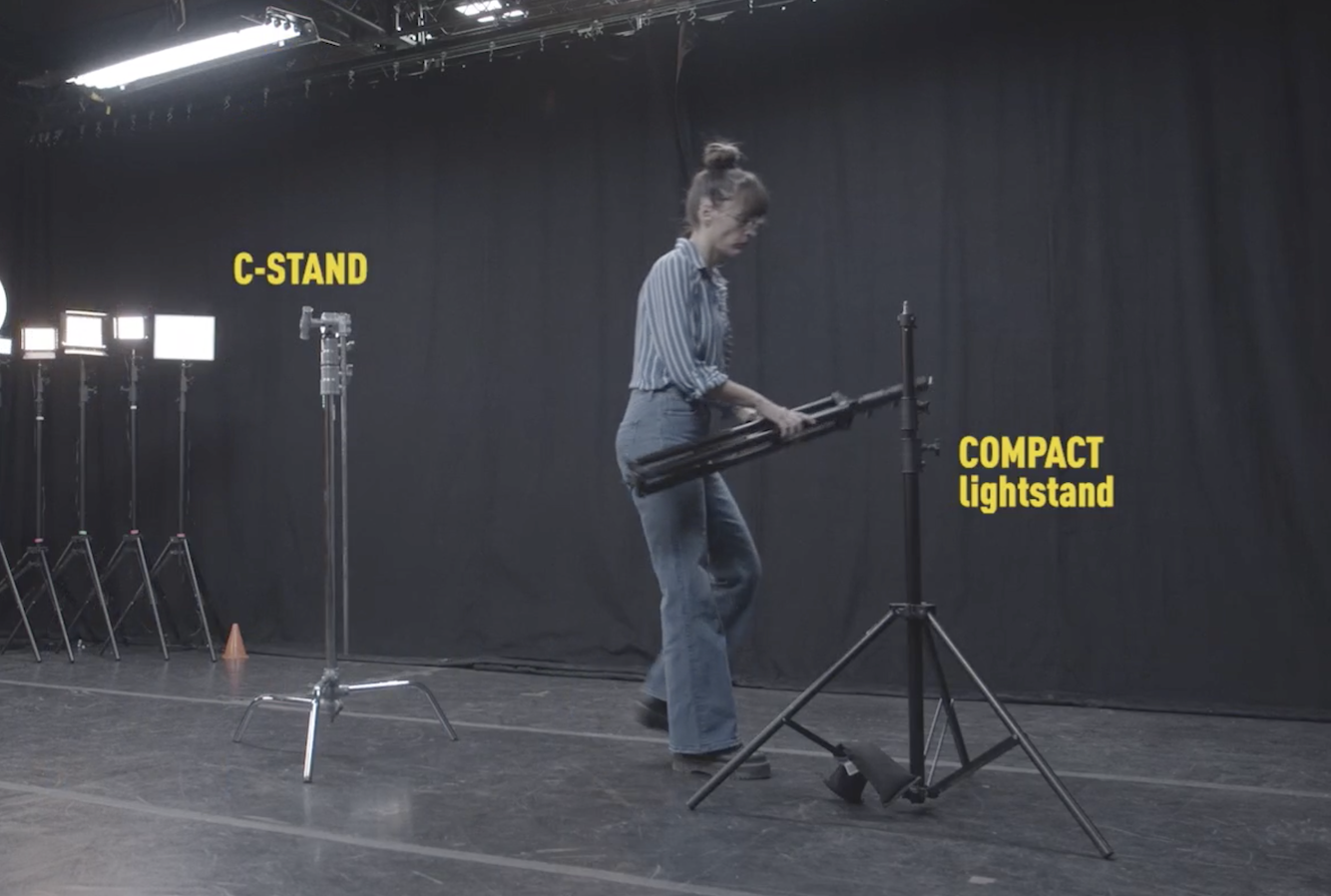

(Above) Student Ryan Kenny during the Grip and Lighting class.

(Left) The Also Sisters during class. (Photos: Sonia Albert-Sobrino)

Rolling with It

For a discipline that largely focuses on the art of making digital media, the necessity to deliver education mostly online could seem easier for the Department of Film & Media Arts at first blush. And perhaps in some ways it was — many members of the faculty are experts with film equipment and editing, which made recording lectures possible.

But possible does not mean easy.

In fact, Miriam and Sonia Albert-Sobrino, twin sisters who are alumni of the department’s graduate program and now are Assistant Professors, spent roughly 550 unplanned hours adapting their delivery to either stream to students’ homes or to project live demonstrations of small intricate techniques so the small number of students in class could be safely distanced and still see the complexities of a procedure. Assistant Professor Michael Edwards was inspired by the approach and was fortunate to use their set-up to teach hand-drawn animation from overhead while simultaneously streaming a classical talking head view.

It’s brilliant, but very complex.

“What, on average, used to be a two-hour process of setting up cameras, lighting gear, etc., before class became a four-hour undertaking involving implementing a multi-cam stream system to run our classes similarly to a live broadcast, feeding through Zoom video signals originating anywhere from two to six cameras,” Miriam said.

Albeit laborious and time-consuming, the Albert-Sobrino twins (the Also Sisters) found it to be incredibly satisfying and rewarding. Perhaps that’s partly how they sustained making hundreds of hours of sophisticated new teaching material that will have purpose long after our need to physically distance ends.

Of course, having even infrequent meetings of small numbers of students in classrooms and on campus to rent film equipment took immediate, thoughtful, and careful planning. Luckily for the department, it has Specialty Media Coordinator and jack of all trades, Jennifer Humphreys. From re-arranging classroom set-ups to rigorous new cleaning, sterilizing, and renting procedures, Humphreys continued to work mostly on campus ensuring students could safely access the spaces and equipment they needed to continue their coursework.

And there are others who worked painstakingly to adjust and who found success with new methods of engaging students. While Assistant Professor Ha Na Lee candidly admits teaching online is out of her comfort zone, she noticed that some of the shifts actually catalyzed more vibrant discussions among students and engaged them in new ways.

“One thing I realized,” she said. “Is there are some good aspects of online teaching that I would

like to permanently incorporate.” In addition to the robust dialogues and flexible schedule for busy students, she noted the value of video tutorials for students who benefit from the ability to stop, rewind, and re-watch.

It seems there are no shortage of reminders of the multitudinous power of film and media. ■

Still from performance video of the University of Utah Chamber Choir led by Professor Barlow Bradford.

Practicing Safe Singing

As the pandemic unfolded, singing in large groups was among the first and most fervently scrutinized activities, along with the other ways of making music that produce the dreaded aerosol emissions which can transmit the coronavirus.

“Choirs got a disproportionate punch from COVID-19,” Barlow Bradford halfway joked. He’s a Professor of Choral Studies and the Ellen Neilson Barnes Presidential Endowed Chair for Choral Studies. “When two members of a chamber choir in Washington died in early March 2020, everything had to be shut down. We realized we couldn’t sing in close quarters and be safe. We were flattened.”

And it was devastating. It took some time to grapple with this new reality, especially while seeing the clever but not stellar work being made remotely and online by other choirs around the world. Each vocalist would sing the piece and someone would edit them all together, and it was an amazing feat to the untrained ear. Bradford’s aren’t.

“I would almost rather not make work if it can’t be artistically outstanding,” Bradford said. His stance makes sense; one doesn’t produce world-renowned choirs by accepting mediocrity when things get challenging.

But when Associate Professor/Lecturer of Music Technology and Composition Mike Cottle came to Bradford with a “crazy idea,” Barlow’s ears perked up.

Soon enough, they were hardwiring microphones, video monitors, and headset jacks in 10 adjacent practice rooms and a classroom, and then connecting that all to Bradford’s office in the expansive David Gardner Hall. Bradford’s office became command central for the Chamber Choir with monitors, cameras, his piano, microphones, and switchers.

This hardwired set-up allowed them to interact from their individual spaces in real time with no latency. Each member of the choir could hear and see Bradford and his piano and each other.

“So much of singing is actually listening and watching,” Bradford explained. “Singers take cues not just from me but their counterparts — and we had managed to make this work without being in close proximity. It was incredible. I thought, ‘Now, I can run a rehearsal.’”

And they did. In fact, the chamber choir was able to produce 14 incredibly powerful works by filming each student as they sung synchronously and editing all the videos together for a full, ethereal, and truly striking composition unlike anything seen before.

Despite the amount of work and complexity, Bradford is committed to this new artform.

“What’s unique about this versus a live performance, is that our audiences can sit down wherever they are with a good sound system or headphones and get lost in a wonderful experience — time and time again. I want to make more work that lives on forever.” ■

Babcock Theatre. (Photo: Todd Collins Photography)

Screenshot from the Department of Theatre’s first show of the season, “The Night Witches,” by Rachel Bublitz, directed by Alexandra Harbold.

Improvising and Adapting

When the University of Utah announced it was going remote in March of 2020, the news landed hard.

“The shift came so suddenly that for a moment I had absolutely no idea how this would even work,” said Assistant Professor and Co-Head of the Actor Training Program in the Department of Theatre, Rob Scott Smith. “It was like taking one step in front of the other and hoping that the ground hadn’t suddenly fallen out from underneath.”

Improv at its finest. And, really, what is theatre if not an exploration into the unfamiliar and the practice of performing collaboratively within everchanging bounds?

“A given semester might offer courses in dance, construction, sewing, singing, lighting and sound design/programming, acting, movement, and dialects as well as traditionally academic’ courses with class sizes ranging from six to well over 60,” Aaron Asano Swenson, Theatre’s Communications Coordinator, said. “All of this had to be translated into new instruction modalities.”

A new Safety Committee, composed of faculty and staff from across the department, spent the summer devising plans for a safer return in the fall. But theatre thrives on interaction, and the department’s spaces and equipment were designed to be shared.

Cami Sheridan, Office Manager and Assistant to the Chair, was in the thick of it. After facilitating the recent transition to a new Interim Chair, Sheridan was well-prepared to work with outside departments and administer COVID policies, while managing the schedules for dozens of spaces in multiple buildings.

“It was a huge learning curve,” Sheridan said. “Overall, I’m appreciative of the Safety Committee members and the rest of our department for keeping our community’s safety as the top priority, but remaining optimistic and creative in the ways we teach, learn, and share our art.”

Another Committee member, Assistant Technical Director and Scenic Charge Artist Halee Rasmussen, prepared the spaces themselves, determining new occupancy limits and installing tools for distancing and hygiene.

“Most of our classes involve practicums and specialized equipment,” Rasmussen said. “Beyond cleaning of desks, it becomes cleaning acting furniture, ballet barres, lighting instruments, power tools, dance floors, sound equipment, etc., after every class.

Then, of course, there were the actual shows. Moving the season online was a phenomenal feat: the previously-canceled “Tartuffe” was restaged and prerecorded, while for “The Night Witches” and “Henry V,” sets, props, costumes, and lights were delivered to the actors to allow them to perform live from home.

“It was remarkable how the theatre community came together to find a way forward,” Smith said. “It’s still a challenge, and it’s not always ideal, but I have found success in embracing the technology and the limitations of shared space in creating new opportunities for our students.”

And as Swenson said, “The response was a testament to the kind of collaboration and problem-solving capabilities you can find in theatre artists and theatre educators in every city in every country, pandemic or no.” ■