By Ava Crane

As a visual artist, curator, and museum professional, Nancy Rivera brings iteration, intention, and her lived experience to her work. During my conversation with the multi-talented artist and Director of Planning and Program at Utah Museum of Fine Arts, I gained many insights applicable to both new and experienced artists alike.

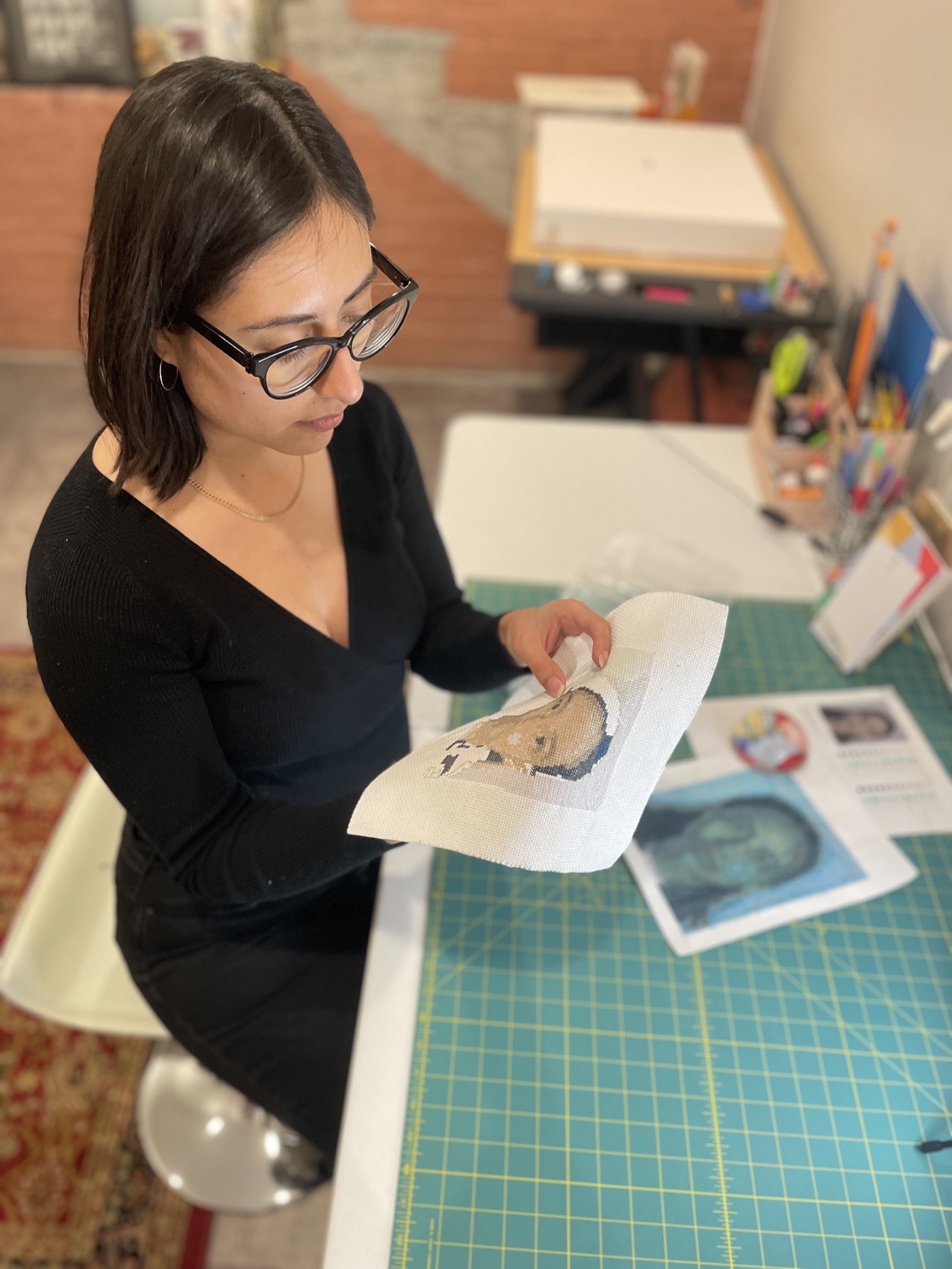

Rivera’s work includes "Family Portrait," a series of cross-stitched portraits based on the photographs used for her family members’ identification through the immigration process, and No Present to Remember, photographs on broadcloth made into sculptural objects using salt from the Great Salt Lake.

Rivera’s evocative works are often built out of inspiration and experimentation. The idea for "No Present to Remember" came to her after she wanted to go beyond the 2D constraints of photography and was inspired by seeing other artists bring photography into the third dimension.

“I always labeled myself as a photographer, but always saw it as a tool, not the end product…” she sFamily Portrait, 2020. Nancy Riveraaid. “It is always very one dimensional in many ways, so I wanted to push the medium into being something different.”

The idea for the sculptural forms came to her in a dream. Once she had the idea, she experimented with different forms. “I went to the store and bought this piece of cotton,” she explained. “I started playing with it and I didn’t have any images at this point. I was just trying to see if I could make fabric sculptural in a way that was kind of unexpected.”

Family Portrait, 2020. Nancy Rivera

Family Portrait, 2020. Nancy Rivera

Much of Rivera’s work has been a process of experimentation and self-discovery. She completed her BFA at Weber State and later attended the University of Utah Department of Art & Art History for her master’s program. Over her career as an artist, she has continued the refinement of her artistic process. “…what you are creating then [as a student] is not representative of who you will be once your work matures,” she said. “It takes a long time to get there and really understand yourself as an artist. There is still a lot to discover about yourself as person that will inform your art.”

Rivera has a unique perspective as she has been on both sides of rejection when it comes to art. As an experienced juror and curator, she can’t overstate the importance of being able to both speak and write about your own work. “Something I see a lot is people not knowing how to write about their artwork,” she said. “Know that you have to spend a lot of time thinking about what your art is saying and learn how to speak about it concisely and smartly and in a way that will pique people’s interest.” Being able to not only describe your work in accessible terms, but to also be able to tailor it to your audience is an essential skill.

"It takes a long time to get there and really understand yourself as an artist. There is still a lot to discover about yourself as person that will inform your art.”

While feedback is essential to growth, Rivera shared that it is important to not take rejection to heart, because it isn’t always about the quality of your work. She explained that jurors for exhibitions will often be handling hundreds of works of art. “I usually start off with saying no to the things that absolutely don’t fit, but then from here you see what mixes together and what stands out,” she said. “A lot of times it is not because your artwork is bad that you get rejected, it is simply because it didn’t fit the overall idea of the project.”

Sometimes a work isn’t selected, because of variety of factors due to the show’s vision, scale, timeliness, audience, and more. She also speaks to how willing people are to help. More often than not, reaching out to artists, professionals, jurors, or curators for feedback won’t hurt and if they have the chance, it could help to get feedback on why your work or application was rejected.

At the root of Rivera’s artistic practice is intention and being able to clearly communicate meaning whether in administrative work to building a portfolio and more. As a curator that favors concise exhibitions herself, she is conscious about finding the through line in her own work to create a sense of focus and self-awareness about her artistic goals. She recommends artists to rather than focus on being as broad as possible, to instead ensure a strong sense of artistic focus and to be selective about what does and doesn’t fit within that focus.

Her lived experience of immigration is a clear and valuable focus in both her artistic and administrative work. In her time at the Utah Division of Arts and Museums, she was able to build up the artist fellowship program. The program offers support to individual artists, but prior to Rivera, the program tended to award to mainly white and established artists. Rivera sought out local, experienced, and talented jurors of color to increase the diversity amongst fellowship recipients. As a result, the fellowships welcomed more women and people of color.

“Having that awareness really helped shape things differently and make people aware that there are artists with that are coming from different places,” she explained. “By that I mean immigrants, undocumented people who need access to the support that we offer, but we need to talk about it differently. It was really cool to see tangible change through small steps that were really intentional.”

ArtsForce Takeaways:

-

Experimentation and iteration are important to a healthy artistic practice.

-

Learn how to write and speak about your work.

-

Don’t take rejection to heart and reach out for help from professionals.

-

Be intentional with what you want to communicate.

-

Your lived experience is valuable.