The Black experience in ballet, which certainly isn’t singular but is an area of important inquiry, is one Joselli Deans knows well. A dancer for over a decade in Dance Theatre of Harlem under the direction of Arthur Mitchell, and an accomplished dance historian and consultant, she knows this vital history firsthand.

We spoke with Associate Professor Deans, who has recently joined the University of Utah School of Dance, bringing incredible depth of knowledge and experience to our classrooms and studios.

This informal conversation was too rich to condense, so this time, we’re sharing the nearly full transcription with you.

Emeri Fetzer: Let’s start with your early childhood interests and how you discovered dance.

Joselli Deans: I grew up in Brooklyn, New York. I have a Haitian background — my parents, Rene Audain and Anna Cassagnol Audain, are from Haiti. My mother tells me that I stood on my toes all the time. She doesn't know if it was to get out of the crib, or if it was the start of the dancing. There was a lot of music and social dancing at home.

When I was five, my cousin was taking my second cousin (who was a year older than me) to ballet class and said to my mother “Why don't you bring Joselli?” She quit three weeks later, and here I am.

My father had been an actor in Haiti. There was a great influx of Haitian people in New York City in the late 60s because of the political situation with [Hatian politican François Duvalier] Papa Doc. He felt like there needed to be entertainment for them, particularly since many of them were not yet English speaking.

He got a bunch of his acting buddies together from Haiti and started a company, called Theatre Choucoune. I was 7. They did some known plays by Molière, some Haitian plays, and he also wrote his own. Soon, he decided that wasn't enough. He was not a dancer, but he became the executive director to the dance part of the company. He got a choreographer to come in and be the artistic director for the dances.

So, my training started with three folds: I did Haitian dancing in my father’s company, tap, and ballet — so I had the European, the African-based, and the hybrid all between the ages 5 and 7.

Lillian Roberts, who owned the Utica Academy of Music and Dance where I started, asked my mother if I would do Haitian dance in my first recital. One of the women in my father's company taught me a solo, and I did it. My first recital was at the Brooklyn Academy of Music at the age of 5.

Fetzer: How did you get connected with the Dance Theatre of Harlem School?

Deans: My father discovered we had a neighbor named Charles Moore. He was a famous modern dancer, and he lived a block over. He guested at my father's company. As the only child in the company, I used to do the little solo numbers so people could change into the next number.

Charles and his wife, Ella Thompson Moore, saw me dance and thought I was talented. My mother and I ran into Ella on the street (she’s still with us by the way, living in NYC. She’s 92!). She asked what I was doing. At that point, my mother had pulled me out of the dance school because I was spending my entire Saturday there, and it was lots of costumes, three recitals a year, and lots of money.

Ella said, “Well, why don't you take her to Arthur [Mitchell] up at Dance Theatre of Harlem. He just started a school.”

My mother would ride with me on the subway. I started in the summer — I think I went three times a week during that summer. They were still at the Church of the Masters. The following year, they moved up to 466 W 152nd street. I was one of the first to be in the new building.

I was, as he used to say, dependable, consistent, disciplined, and worked hard. I wasn’t as flexible as ballet dancers should be. I was quick. I turned well, I could jump. I learned quickly.

Fetzer: What are some of the favorite moments from your time there?

Deans: Dance Theatre of Harlem started a short-lived (maybe three years) junior company that I was in — so that was quite a thing. And we did some special performances with the company and without them. One of our big performances was at the convention center in Atlantic City where they used to have the Miss America pageant. We performed for the Urban League. Celeste Holm was there, Ruby Dee was there, all these famous people – I have all their autographs in a little book I kept with me.

And then we had a command performance in the dance studio for her Royal Highness Princess Margaret and her husband Antony Armstrong Jones, Earl of Snowdon. He was a photographer, and he took a lot of pictures of the company in the early years.

Another moment was when Miss Tanaquil Le Clercq, who was Balanchine’s last wife, got polio.

Mr. Mitchell was in New York City Ballet with her when she was dancing, and he convinced Mr. Balanchine that she should come and teach at our school. So, she taught in a chair and I used to demonstrate for her in the classes. She and I both spoke French, and she would speak to me in French — I think that empowered her in some ways, because she couldn’t dance anymore. I was very honored to be her demonstrator.

I liked watching the older dancers. I remember sitting on a step there into the studio. We were allowed sometimes to come in and sit there and be very quiet and watch.

I watched incredible dancers.

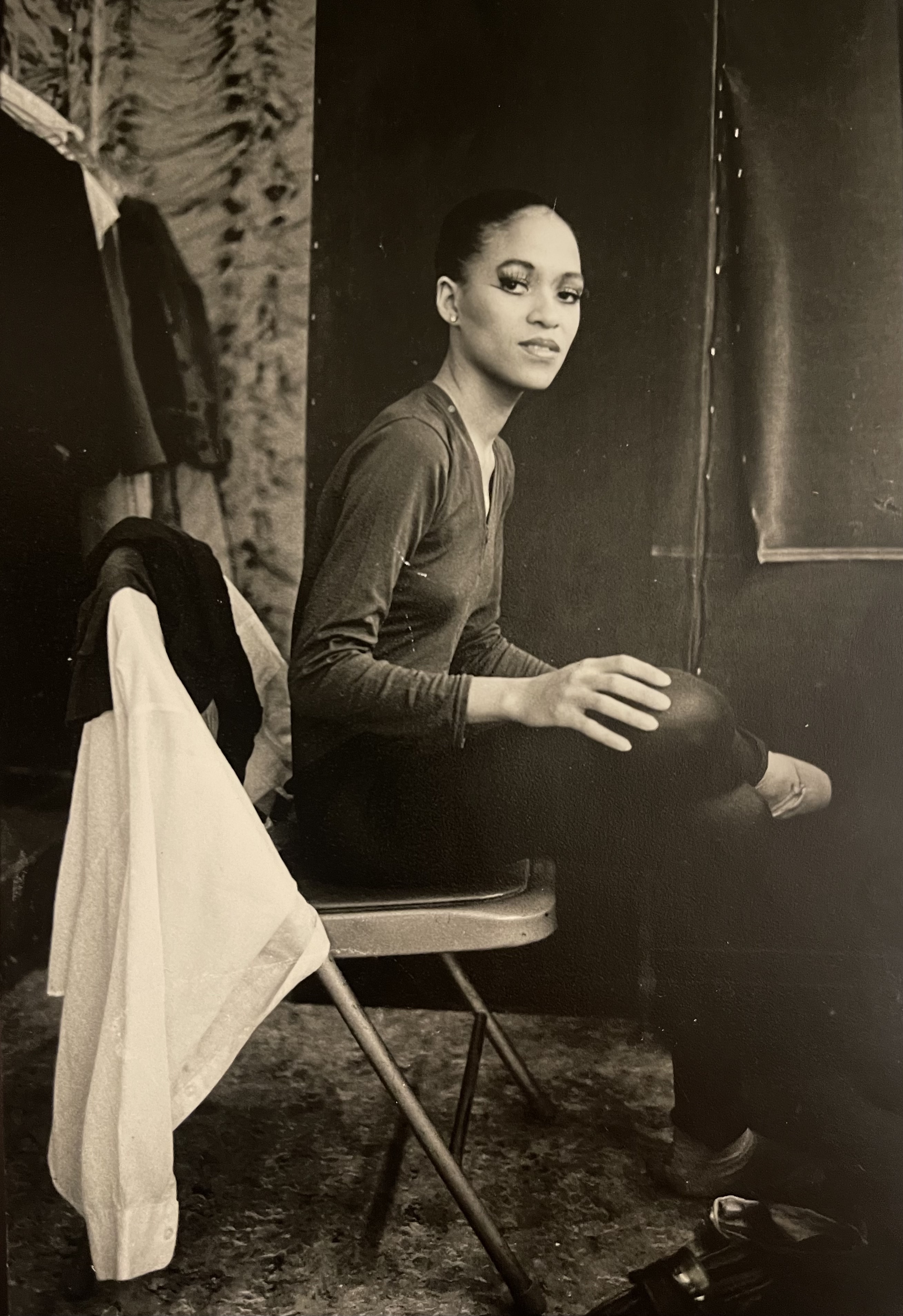

Fetzer: How did you end up transitioning to the company? Dressing room at New York City Center 1983 | photo courtesy Joselli Deans

Dressing room at New York City Center 1983 | photo courtesy Joselli Deans

Deans: I got to the highest level that there was for school students. We had class for two hours a day, every day. I was hiking from high school in Brooklyn to Harlem every day for a two-hour class and back. I consider myself the Forest Gump of Black dance. I just happened to be in the right place at the right time. When Mr. Mitchell was putting together a special class of people, he wanted apprentices.

I walked through the office and he said, “Oh no you can't, because you don't get out of school early enough.”

I said, “I'm a senior. I get out at noon.”

“Can you be here by 1:30?”

I said, “Yes, I can.”

So, in my senior year, I performed in DTH’s first City Center season. I only did two ballets, but that's okay. That's a good start. At the end of that school year in July, the company was going to England and Ireland. I was sort of iffy – the company was an ensemble company, around 30 dancers, but he was starting to expand. I went, but I also helped with the wardrobe as an extra hand.

I was the standby dancer. One night, our lead dancer in “Serenade,” Lorraine Graves, got sick and then somebody had to take her spot. So, I had to go into the corps to replace the girl that was becoming the lead, Karlya Shelton. We didn't use titles, but in ballet terms, she was the highest of the corps. In this dance she did all the extra stuff.

My first performance of “Serenade,” I didn't even get a rehearsal. I got a look through on the video. I knew the steps because I was an understudy, but I had to learn her spacing. It was a lot of pressure. But I got through it. I made a big mistake, but I fixed it. And Mr. Mitchell was very impressed. I said, “I'm sorry I missed the cue.” And he was like, “No, but you fixed it.” I got his attention.

I just worked my way up. I was a corps dancer. I was not particularly fantastic in any way. I was, as he used to say, dependable, consistent, disciplined, and worked hard. I wasn’t as flexible as ballet dancers should be. I was quick. I turned well, I could jump. I learned quickly.

Fetzer: Of course, it is hard to cover all the amazing memories in your 11 years dancing at DTH. But can you share a few highlights?

Deans: DTH was a traveling company — a lot of ballet companies now are not. But DTH was on the road all the time, and so in the 11 years I went to 33 countries and five of the seven continents.

I danced on some of the major stages in the world: the Royal Opera House, the Kennedy Center, the Civic Auditorium where they used to have the Academy Awards before they built the Kodak. Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris…

And this is not necessarily famous, but one of my favorite movies as a little girl was “Sound of Music.” I danced on the stage at the end of the movie. I couldn’t believe I was on the stage where Julie Andrews sang. We danced at an amphitheater that Herod from the Bible built is Israel, the Met in New York, and the 1984 Closing Ceremonies of the Olympics in LA.

Fetzer: Who were some important mentors?

Deans: Well, my father was a great influence. Not so much for my dancing itself, but for understanding history. Our apartment had a long hallway lined with bookshelves. I was a reader when I was a kid. He bought me books all the time, and some about dance. I got this historical sense. And then because DTH was “the first permanent Black ballet company,” I really had a sense of history.

Mr. Mitchell, of course, was a mentor. He pushed me. He saw something in me I didn't see in myself. He said that I would be a great teacher. I must have made an ugly face when he said that. Because back in those days, the adage in dance was, those who can't, teach. I was hurt. He said, “Why is it that when I say you're gonna be a good teacher, you hear I'm saying you are a bad dancer? That’s not what I am saying. What I'm saying is you have a gift, and you need to hone it.”

In 1986, the company was invited to tea at Buckingham Palace, but there were too many of us to go. So, he only took the principal dancers, which made sense. But he or the principal dancers would teach the warmups. With them all gone, who’s going to teach? So, he comes in to teach class that morning and goes, “Okay, I'm going to Buckingham with the principals, Joselli's teaching the warmup tonight.” He didn't ask if I could do it, just did it. So, I started my teaching career with warmup for the Dance Theater of Harlem. I was in awe.

Another influence is a man named William Griffith. We called him Mr. Bill. He was the company teacher from 1980 to 1985. He very much made me the technical teacher that I am. The way I teach from him.

And Kathy Grant, a woman that learned Pilates from [Joseph] Pilates himself. She was DTH's first company manager, and she also taught special exercises, which were based on the Pilates mat work, but she added dance movement. Because I was not flexible, she helped me get the range that I needed to survive as a dancer.

Many of the dancers who got injured would wind up going to her. She would teach me how to do the therapy for them when we would go on the road. Her studio was in Bendel's department store, which was a very swanky place on 57th Street in NYC. She made a deal with my parents. We just paid the store fee and then I would come in on Saturdays, do my workout, but help her when she needed an extra set of hands.

Dance Theatre of Harlem was on the road all the time, and so in the 11 years I went to 33 countries and five of the seven continents.

Fetzer: How did you end up going back to college and on to earn your doctoral degree?

Deans: When I graduated high school and got into the company, I was also going to NYU. There was a program called University Without Walls and I would get credit for my dancing.

I did that for a year and a half. My grades weren’t great, and it was costing a lot of money. I didn't feel like I was getting what I needed out of it. I contemplated quitting.

One of my professors, Sharon Friedman, said, “Look, Joselli, you have an opportunity that dancers would die for. You're dancing with a major company. You're smart, you're hardworking, you're curious. You can always go back to school.” I decided to stop. I went home and I told my father I was quitting, and he hit the roof. It was always a given that I was going to college.

He died in 1986. I left dancing almost in 1990. So, he doesn't know that I went back to school and went as far as I did. I know he would've been really happy.

I am my mother's only child. I was always on the road — that was hard on me, and her.

And then having relationships. I never dated at work. I don't believe in that. If I wanted to get married and have kids, I was getting older. My body was hard to deal with. So I decided to stop. I didn't know what I would do.

But during my career, my spiritual life ignited. I really got interested in how dancing and worship come together. In many other cultures, dancing is based in that. I went and got a degree in theology, and then I was going to go to grad school to put dance and theology together.

I worked at a school with theology and dance, the Institute of Black Catholic Studies at Xavier University. The professors there said, “You won’t get funding to do this kind of work at a graduate level.” I decided that I would go back to school to get a Master of Education so I could teach high school dance in an arts high school. That was the vision. At Temple, they suggested that I do an MFA. I really wanted to learn the strong foundations of pedagogy for dance. While I was doing MEd, the faculty came to me and said, “We want to put you forward for a doctoral degree.” I had never thought of getting a doctoral degree in any form, let alone in dance. But as an African American woman who's getting a free degree where they're paying you to go to school, I thought, “Well, I better do that.”

My father used to always say, “America is the land of opportunity. Don't blow it.”

I got the fellowship. I taught upper-level classes at Temple University as a graduate assistant and as a future faculty fellow. I was at Temple for seven years.

Fetzer: Can you talk a bit about your research and publishing on Black ballet dancers?

Deans: Since I couldn’t do a master’s in dance and theology, I thought maybe I could bring religion and dance together in my doctoral work. Nobody had a background in it in my department. They said, “No, you're a Black ballerina. There's so much to say,” and it's true. There were things happening that were starting to intensify that discussion.

I went to this seminar symposium from Philly to New York called Classic Black — it was about Black ballet dancers before DTH. I had grown up hearing that DTH was the first permanent Black ballet company, and it never dawned on me to ask why “permanent?” I never knew that there were other companies before us. I had heard about certain specific dancers, but not companies.

At this event I heard all the stories about the companies and the individuals. Delores Brown got up and said, “Why can't Black female dancers go into the corps de ballet and work their way up, like everybody else, into principal roles. Why do they have to be principal level just to get in the corps?” My stomach turned over. I decided I would do my dissertation on Black female ballerinas. I selected Janet Collins, who was the first woman to dance with the Metropolitan Opera Ballet. She broke the ceiling. And also Delores Brown, and Raven Wilkinson who danced with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo [disbanded in 1962]. When I went to Ms. Collins, she said no. A woman had just met with her about writing her biography. So, I missed the boat. But my dissertation outlined the other two.

I really had to think about how to talk about racism and ballet. Ballet is the Sacred Cow of Dance in America. I knew I’d have to dot my Is and cross my Ts. I did a lot of research about these companies and dug deeper to do background so I could present my case. That turned out to be 100 pages of my dissertation. It was too long for a chapter. So, it became chapter three and four of my dissertation, and each of these ladies’ orals history became five and six, and then the concluding chapter was seven and the follow up was eight and the whole thing was 400 pages long.

Then things started to happen. I presented a paper at Dancing in the Millennium, which was probably the biggest dance conference in history. I don't know if there's been one since where every dance organization participated. In that paper, I compared reviews of DTH, American Ballet Theatre and New York City Ballet performances of “Swan Lake,” and how critics use different language with our company and other companies. I left all the critics names out of the text, although of course they were cited. I explained that I'm not picking at these critics per se, but the whole system.

One of the critics was in the room. She got defensive and the whole room chimed into my presentation. It was a good feeling.

Later I was invited to be a consultant for the film “The Black Ballerina.” I presented “Blacks in Ballet,” and that's how I started to be known for this topic.

I wound up teaching Catholic high school for seven years, still trying to stay connected to the dance world. Somewhere in the midst of that, Virginia Johnson from the Dance Theater of Harlem asked me to be part of The Equity Project. There were 20 companies that participated. I presented some Blacks in ballet history as part of our four women team equity work with these companies. Christopher Alloways-Ramsey, Sean Carter, and Joselli Deans in "Sleeping Beauty," School of Dance Utah Ballet concert | photo Todd Collins

Christopher Alloways-Ramsey, Sean Carter, and Joselli Deans in "Sleeping Beauty," School of Dance Utah Ballet concert | photo Todd Collins

Fetzer: What impact do you feel like you specifically have in this equity work with organizations?

Deans: I think that I've put forward for them a history that they were unfamiliar with and added context it in a way that they needed to understand it — to understand the idea of Blacks and ballet.

When ballet started to develop itself in America, we were a segregated society. So white people had no idea what black people were doing. But Black people have been studying ballet as long as white people have. It's just nobody knew about it.

And then another comment that I make — particularly back then, not so much now because things have changed and evolved — but a lot of the people that taught Black dancers were Europeans because the white people wouldn't take them on. Europeans would teach them, many times, privately because they couldn't have the Black kids in the school. So they're not only getting European training, they're getting it privately. So the level of some of these dancers, these older dancers, was incredible. And then they opened schools, and they taught people. And then that generation of dancers got to dance in the 40s, 50s and the 60s.

Some went to Europe where they could have a career. Or they were in the Black ballet companies that were short lived in the 50s and the 60s until Mr. Mitchell started DTH in ‘69. I explain that we have documentation that Blacks were studying ballet since 1919.

I don't own Blacks in ballet, but I was one of the individuals who began really delving into it. Now that I'm in this position, in a Research 1 institution where I can do research, I have so many different projects in my brain. I am excited to start.

I think that I've put forward for them a history that they were unfamiliar with and added context it in a way that they needed to understand it — to understand the idea of Blacks and ballet.

Fetzer: What are some challenges that young dancers are facing today?

Deans: The arts have become a business model. It's all about the money. Now, don't get me wrong, we always needed money as artists. But the cost of living for you to dance — you could get two or three roommates and afford to live a decent life, and you can't do that anymore.

Young dancers have to be patient with themselves. They have to realize that although quantity seems to be what's important, both in money and in technique… for the people that really succeed, it's about quality. The quality of your choices, the quality of your dancing, the quality of life that you want to have. That's what gives you longevity. That's what gives you joy and satisfaction.

It's all about the tricks now, and that's not artistry. Artistry will take you into other places, and other levels. I was trained to be an artist. And that's why I can now be a dance historian and all the other things. It’s the level to which I was held –– it was about excellence.

FULL BIO

Joselli Audain Deans, originally from Brooklyn, NY, joined the Dance Theatre of Harlem after receiving most of her training at the company’s school. During her career with DTH she danced numerous roles, including “the accused as a child” in Agnes de Mille’s "Fall River Legend."

A scholar and an artist, she holds a doctorate in Dance Education from Temple University. Her dissertation entitled "Black Ballerinas Dancing on the Edge” documents the lives of Delores Browne and Raven Wilkinson and analyzes how biased ideas and practices impact African American ballet dancers, then and now. She has taught dance technique at Philadanco and several academic institutions including Bryn Mawr College and Temple University; presented her work at scholarly conferences, including at Corps de Ballet International, Association for the Study of African American Life and History, and Collegium for African Diaspora Dance; and her research is published on Arthur Mitchell’s archival collection on Columbia University’s library website curated by Lynn Garafola and in "(Re:) Claiming Ballet" edited by Adesola Akinleye. She has served as a consultant for several institutions and projects including for Dance Theatre of Harlem, American Ballet Theatre, New York City Ballet, School of American Ballet, San Francisco Ballet, Charlotte Ballet, the Dance Oral History Project for New York Public Library, the documentary "Black Ballerina," and was a design and facilitation team member for the Equity Project: Increasing the Presence of Blacks in Ballet.