WRITTEN BY MARINA GOMBERG

PHOTOS TODD COLLINS

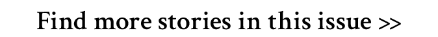

Department of Theatre Professor, Sarah Shippobotham, grew up in Bristol, England in what she describes as a very women-centric environment. She went to primarily all-girl schools taught by female teachers, and that experience was, in part, what informed her interest in women-driven political theatre.

Her lauded so-far 20-year career at the University of Utah and international work as a respected Dialect Coach (for films such as the “The Hobbit”) speak to her professional success, but it’s her effervescent kindness and sensitivity that might ultimately make her greatest mark.

She is a warm and disarming presence, so it’s easy to trust her sincerity when she talks about having always been interested in ensuring the safety and comfort of those with whom she works. Yet, it’s only been recently that the world of theatre has made a clear and concerted effort to do the same — at least as it relates to creating and performing scenes of intimacy.

“I’ve always been of the mind that sex and violence are choreographed,” she said. “But violence is the only one where people — until recently — have been paid to do that specific work.”

And not a moment too soon.

The investigations, resources and organizations dedicated to raising the visibility of ideas about consent on stage are, as one might imagine, a response to the powerful #MeToo movement, which is driving critique and conversation about the pervasive nature of exploitation and harassment in the workplace.

Shippobotham remembers a particularly important moment when things came to a head in the theatre world. It involved a celebrated actor at Profiles Theatre in Chicago who was being outed by former castmates and crew members for his unprofessional (unethical) behavior with his colleagues.

They bravely described to the media the horrific, painful, threatening interactions they’d have on stage with him that seemed to go far beyond the script, far beyond their boundaries, and far beyond what any person should reasonably expect from another human being.

“It was situations like that one that made me sit up,” she said. “The sense of safety I’ve so often enjoyed cannot be assumed for anyone else on any given day.”

And that’s when she began seeking resources and training for intimacy directing in earnest.

“I wanted to be one of the people who was going to take responsibility to fix the status quo,” she said.

What followed for her was unexpectedly and overwhelmingly powerful.

Her eyes filled with tears as she remembered an exercise in which she and some eight other women engaged at a workshop hosted by a British version of Intimacy Directors International (IDI) in December 2017 in London (no men had signed up to participate).

She described how they were instructed to stand in a circle (and unlike the common theatre exercise where someone would cross the circle asking to be ‘helped’, which the other person could not refuse) the person approached had the flexibility to respond “no” to the request.

For as simple as that sounds, it was profound.

“The notion that we could say no,” she said shaking her head and pausing in an attempt to regain her composure and steady her voice. “That that was a new possibility very much illuminated the problem.”

She went on to describe that success in the theatre world is often predicated on a person’s willingness to always answer “yes.” She says that’s even more true for women, lest they seem “difficult.”

The theatre has always existed to reflect society, and in this way, it was succeeding without intentional scripting.

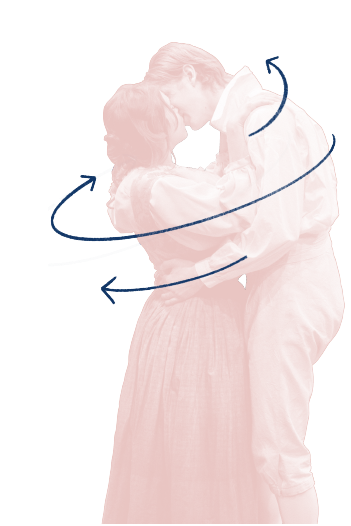

For whatever reason — discomfort, disinterest, or disorganization — many directors have long allowed intimate scenes to be explored by the actors without much assistance or interference. But without planned and specific choreography, too much can be left unsaid, unconsented, changed over time, or exploited.

Shippobotham says this is an example, a place, where language is so critically important. Choreographing a scene using anatomical language rather than euphemisms and calling scenes by titles other than sexual names, takes the potential for fear about the vulnerability of doing this kind of work out of the rehearsal room and re-focuses the work on the story that’s being told.

But knowing and using appropriate language is not at all the only training an intimacy director receives.

The IDI has just announced an apprenticeship program that will start this coming April. They will be looking for 10 apprentices and the requirements for eligibility to apply are stringent. Areas of personal study that can benefit an apprentice in-waiting include: Mental Health First Aid Training and knowing the Federal, State, and Municipal laws surrounding nudity in the area one works.

While the entire process of training could take a person years to complete, Shippobotham is taking every chance she can get to bring about the change she wants to see. She’s taking local and international workshops, she’s bringing those learnings into her classrooms and productions (including scenes in the department’s production of “Our Country’s Good” that she directed), she’s providing her developing knowledgebase and experience to professional theatres, and she’s reaching out to the experts when she wants or needs the additional support.

“We are working to maintain one of the premier acting schools in the country,” she said. “We’re preparing our students to work in New York, Chicago, and London, and if all we do is safe work, we’d do the disservice of never providing them the opportunity to learn how to respond or to identify their boundaries.

“It’s our responsibility to make these students ready for the world — not just ready to make good theatre.”