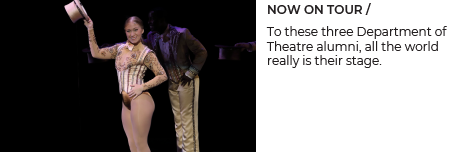

Sama Zitkala-Ša photographed by Gertrude Käsebier ca. 1898. Photographic History Collection, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

WRITTEN BY JULIA LYON

The Untold Story of How Music Shaped Zitkala-Ša’s Life

When people think of Zitkala-Ša — if they’ve heard about her at all — they think of an activist, a Native American woman who spoke out against the residential school system and advocated for Indigenous and women’s rights.

But what Misti Webster discovered, while researching her University of Utah graduate thesis, is that her musical training and skill as a singer, pianist, and violinist dramatically shaped her life.

“I think people need to know she was a musician first and foremost,” said Webster, who graduated with an MA in Musicology in 2022.

Born in 1876, Zitkala-Ša (also known as Gertrude Simmons Bonnin) began attending White’s Indiana Manual Labor Institute at 8 years old. She was eager to go, believing the school would be in a “more beautiful country than ours,” according to a collection of her personal essays. Her friends were going, too.

But Zitkala-Ša soon discovered her new life was not what she expected.

“The melancholy of those black days has left so long a shadow that it darkens the path of years that have since gone by,” she wrote in “The Atlantic” in 1900.

School of Music Associate Professor Jane Hatter’s graduate musicology seminar on Gender, Music, and Performance in 2021 launched Webster on her research journey. Hatter had seen a Google Doodle in honor of Zitkala-Ša’s 145th birthday. The doodle portrays Zitkala-Ša next to a violin, which made Hatter want to learn more.

As it turns out, she had lived for a time in Utah. Hatter decided to include Zitkala-Ša on her seminar’s syllabus.

“I became fascinated by her as a person,” recalled Webster, who was then a student in the class. “I wanted to know more about her life in general — and not just the part she spent in Utah.”

Sama Zitkala-Ša photographed by Gertrude Käsebier ca. 1898. Photographic History Collection, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

She realized many people had written about the Native American woman, but primarily focused on her writing and speeches. What everyone seemed to overlook was that Zitkala-Ša was also a very good musician.

Being a woman and a Yankton Sioux, Zitkala-Ša had “a lot of limitations on what she could do from a social standpoint,” Webster realized.

“Essentially what I argue in my thesis is she used music as a means to access social or political circles she might not have been able to access otherwise,” she said.

Her thesis, “Music as Means: New Light on the Musical Education and Accomplishments of Zitkala-Ša,” is the first to examine how her schooling and musical training became an important tool in her life.

Webster learned more about the Yankton Reservation in South Dakota where Zitkala-Ša was born and how the different schools she attended may have impacted her. Zitkala-Ša studied at multiple other schools including the New England Conservatory of Music.

While it’s unclear what her first instrument was, Webster believes Zitkala-Ša was predominately a violinist — but also a singer and fairly accomplished pianist. She was educated in Western music and taught to play Bach, Chopin, and other major composers in the Western canon.

“When she entered the Western system, it’s assumed any and all musical traditions she knew from her Native background were squashed,” Webster said.

Zitkala-Ša later taught music at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. Founded by Henry Pratt, the school was the first government-run residential school for Native Americans in the nation. These schools, like the one she attended in Indiana, forced students to assimilate into white culture by making them speak English, cutting their hair, and forcing them to abandon their traditions.

Thanks to a College of Fine Arts Graduate Student Research Grant, Webster was able to visit Carlisle and examine the archives.

“When you actually hold the documents in your hands and … see the photographs of these children, it’s eye opening,” she said, noting that the descendants of some of these children may not even know the photographs and records are there.

Though Zitkala-Ša was loudly critical of the boarding school system, some Indigenous people are similarly critical of her for collaborating with Pratt as an adult. Not only her teaching, but the fact that she toured with him and the Carlisle Band for several months in 1900. She was initially hired as a violin soloist, but Pratt required her to wear traditional Native American clothing borrowed from a museum and to recite the poem “The Song of Hiawatha” by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

“There are definitely instances like that where she was put on display, but she still used all these things as some kind of opportunity to get her voice out there and make certain connections,” Webster said.

Zitkala-Ša moved to Fort Duchesne, Utah, in 1902 with her husband Raymond Bonnin, also a survivor of the residential school system. While living there, she met a local white man named William F. Hanson and she collaborated with him on “The Sun Dance Opera,” which premiered in Vernal in 1913. After being performed throughout Utah, it was eventually performed in New York City in 1938.

Much of what is known about the opera is from the letters of Hanson, who went on to teach music at Brigham Young University. Webster visited the BYU archives, but found many questions remain about the extent of Zitkala-Ša’s involvement. That’s not a surprise to Hatter at the University of Utah.

Misti Webster

Photo: University Marketing & Communications

“In the field of history, in general, we tend to like written documents, and composers are the ones who write written documents,” the Associate Professor observed. “I think it doesn’t really matter if she composed or not — she was part of the process — and the process was collaborative.”

If we abandon the “single genius narrative” of composing music and include more kinds of creators, “we’re likely to get a more diverse view of history,” Hatter said.

Zitkala-Ša’s papers at BYU came from Hanson’s representative. It appears some documents did not survive.

What exists doesn’t reveal how Zitkala-Ša felt about her musical education and career. But Webster was able to review archives at the New England Conservatory and at Earlham College in Indiana, where Zitkala-Ša was a student from 1895 to 1897. She believes those documents, which show what type of music the Native American woman played, show just how accomplished she was.

“Misti did a great job at finding those details other people had missed by taking Zitkala-Ša’s education seriously,” Hatter said. “I think it’s really important to find those lost voices.”

Webster hopes to continue her research on Zitkala-Ša as a PhD student in musicology next fall. What began as a fascination with someone who used to live in Utah has grown into a research interest with a larger purpose.

“I’ve always striven to amplify voices that aren’t much talked about in musicology,” she said. ■