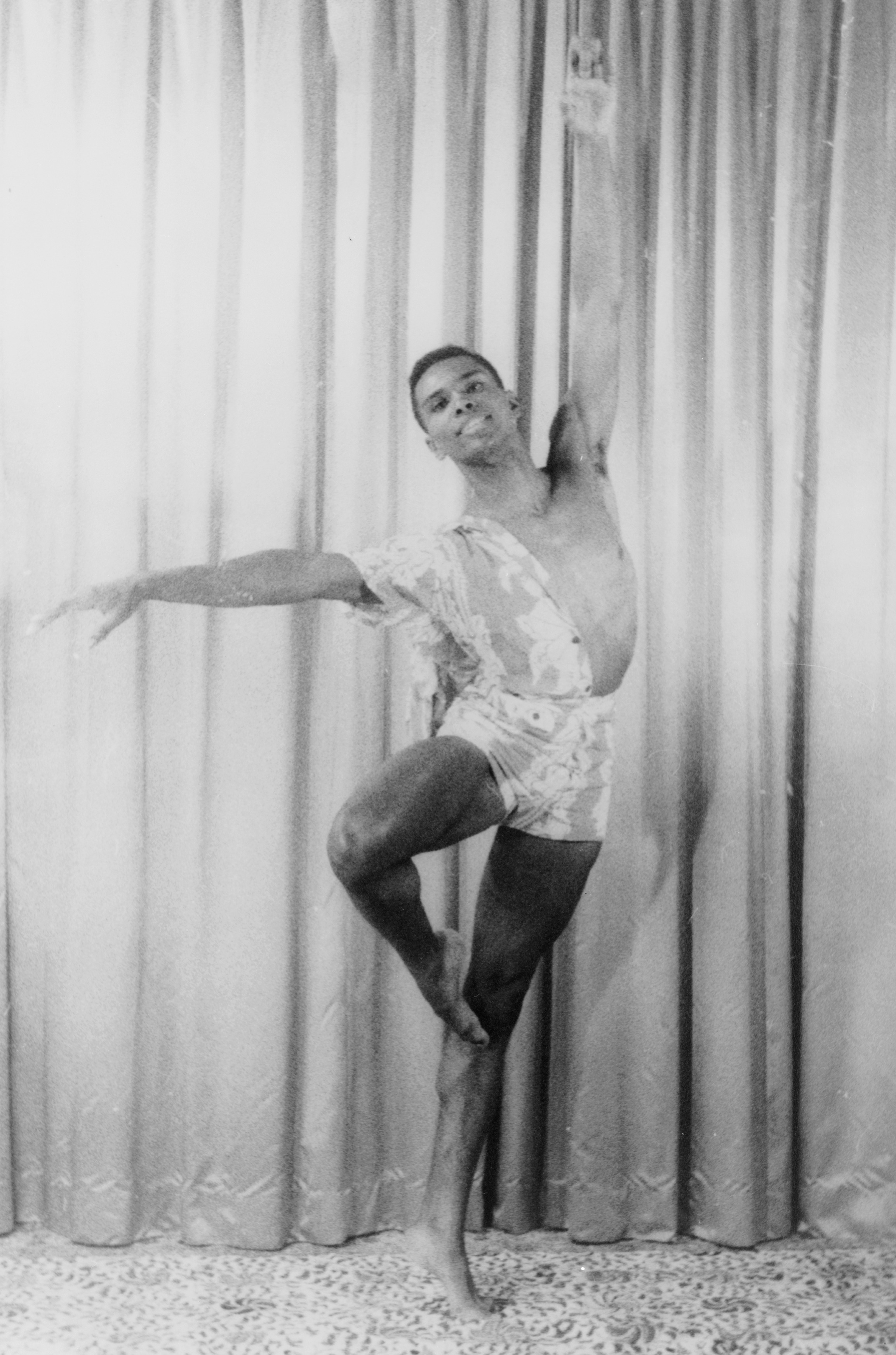

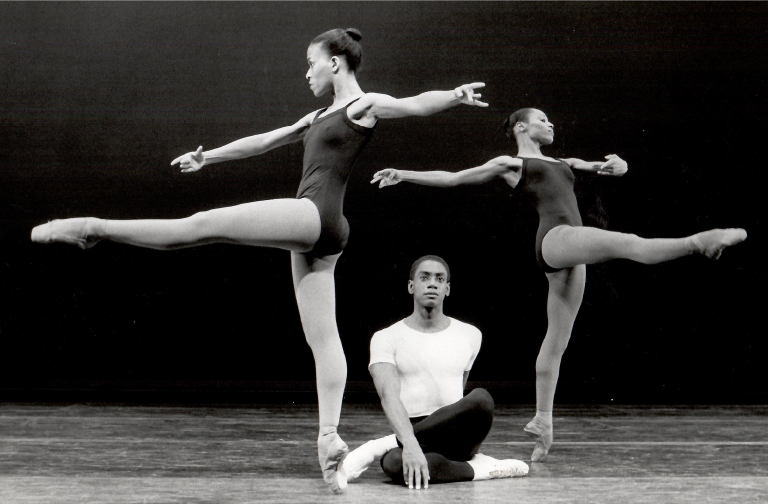

Iconic Black ballet dancer Arthur Mitchell (Photo: Martha Swope)

WRITTEN BY MARINA GOMBERG

That’s a truth that dancer, historian, and University of Utah School of Dance Associate Professor Joselli Deans, PhD, heard the iconic ballet dancer Arthur Mitchell say with some frequency.

Yet, despite the rich history of Black contributions to ballet, when Deans holds up a copy of the most recent popular ballet texts, she notes that it includes but a singular mention of a Black dancer — who turns out to be Mitchell, her mentor, and the founder of the Dance Theatre of Harlem.

Like so many canons, ballet’s history has mostly been told by and about white dancers, choreographers, and companies. Lots of pink tights and European names.

But Deans is an integral part of a movement working to document some of the roughly 100 years of Black ballet history that has been omitted, excluded, and perhaps nearly erased — a process she began with her dissertation chronicling the lives of two Black female ballet dancers: Delores Browne and Raven Wilkinson.

Her excellence as a Black scholar is widely celebrated and she was recently recognized by the U’s Black Faculty and Student Association with its Malcolm X Award of Social Justice award for individuals who have fought for justice in terms of the distribution of equal access, opportunities, and privileges within our campus and whose body of academic work and life promote or exemplify the area of social justice in modern life, bestowed in Spring 2024.

And now, with eight other dance academics, all but one of whom was also a performer with the Dance Theatre of Harlem where Deans danced for almost 20 years, she is writing an anthology about the country’s first and perhaps still most iconic Black ballet: Dance Theatre of Harlem.

She smiled when she remembered how often (albeit unsuccessfully) she had encouraged Mitchell to write his extraordinary story which included him being the first Black dancer with the New York City Ballet, working with the legendary George Balanchine, and being inspired to start his own school and company on April 4, 1968 — the day Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated.

Deans tells the story that Mitchell was about to board a plane when he heard the terrible news and left the airport to be with his community in Harlem.

“I am a fighter, and I fight with my art,” he said. “Each unpleasant experience has made me stronger and more determined to give the world Black classical dancers who have instilled within themselves the attitude that the major distinction between performing artists lies not within the color of their skin, but in their ability to perform. This is why the Dance Theatre of Harlem must exist.”

And he made it so. But his entire story is still yet to be told — a reality Deans hasn’t forgotten.

The last conversation the two of them had before he passed away was when she wished her “Dance Dad” a happy Father’s Day in 2018.

Their relationship had been long and meaningful. The two met when Deans was 10-years old and transferring ballet schools in Harlem. She is a first-generation Haitian American daughter of artists who was fortunate enough to land at Dance Theatre of Harlem where she trained for eight years during grade and high school. She remembers how much Mitchell cared that his dancers were achieving both in and outside of the studio. He wasn’t shy to articulate his high expectations.

“If we weren’t getting good grades, we were out,” Deans recalled. “We knew he loved us and saw our potential. He called himself a ‘benevolent dictator.’ The intent was to make us excellent.”

After graduating high school, Deans joined the company as an apprentice. Within months, she was traveling and performing around the world. She went on to become a full member of the company where she danced professionally for seven years. Mitchell watched her grow up and even got to watch her raise her own child.

Dancers Joselli Deans (left), Ronald Perry (center) and Anjali Austin (right)

(Photo: Martha Swope)

Upon Mitchell’s passing in September 2018, Deans felt that telling his story became, in part, her responsibility. And a few years later, Deans was serendipitously encouraged to apply for a Transformative Intersectional Collective (TRIC) grant disbursed by the U’s School for Cultural and Social Transformation from funding that had been given to the institution by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

Shortly after submitting the grant application to fund her future writing project, Dean’s mentor and friend Thomas DeFrantz, a professor at Northwestern, called her saying he had been offered to do a book and wondered if she might want to collaborate.

And then she heard she got the grant. The stars seemed to align. Again.

The working title of the co-authored book is “Arthur Mitchell’s Love Letter: Dance Theatre of Harlem and its Legacies” and it will be published by the University Press of Florida.

Mitchell had once said, “You are not a line, not a phrase, not a paragraph, not a page… but a chapter in history,” Deans and her peers are making sure of it.