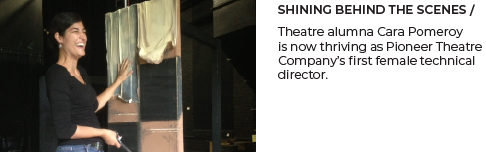

(Left) Elisa Alfonso. Photo: Catherine Heeman

(Right) The airplane logbook documenting unaccompanied children that includes Alfonso’s father, listed as Gilberto Alfonso Flores. Photo: Courtesy of Elisa Alfonso

WRITTEN BY MARINA GOMBERG

Like many young students, Raymond C. Morales Post-doctorate Fellow in Musicology, Elisa Alfonso, had divergent interests while studying at East Carolina University as an undergraduate. She was a flute performance major who picked up a Hispanic studies major, wrote her undergrad thesis on geography, and earned a half-minor in biology.

It was not abundantly clear what to do next with those diverse interests until she met ethnomusicologist and Associate Professor Mario Rey, a Cuban American like Alfonso, who noticed how her curiosities converged in one unique place: ethnomusicology, the study of music in its cultural context.

And so, she went on to graduate school at Florida State pursuing just that and then earned her PhD at University of Texas at Austin.

As the child of a Cuban migrant, she was primarily interested in the culture and context of Operation Pedro Pan, the clandestine relocation of more than 14,000 Cuban children from Cuba to the United States in the early 1960s by the Catholic Welfare Bureau and U.S. government.

Growing up, Alfonso had heard bits and pieces of her father’s emigration story from Cuba. Some of his experience seemed strikingly similar to what she was researching, though he hadn’t known the full context of his U.S. immigration. It was through her investigations that she discovered her dad was, in fact, a Pedro Pan himself.

As a musician, in addition to the historical context of the Cold War and the conditions of migrant camps, Alfonso’s interests were often focused on the documentation — or lack thereof — of the oral and sonic.

“My research, in part, examines music and sound as it shapes the collective memory and the historical narratives of the exodus,” she said. “The other part of my work examines how music and sound help Pedro Pans and their descendants express and process the traumatic memory of their unaccompanied childhood migration event.”

One example was a lullaby called “Señora Santana” about a little boy who lost his apple and a kind woman who gives him another one. Various versions of this song had been sung in Cuban American communities for decades (in fact, Alfonso wrote about many of them for the Library of Congress Blogs in a piece called “Caught My Ear: The Lullaby That Came to Symbolize the Exodus of Cuba’s Children”).

Some versions of the song include a third verse recounting the boy’s dissatisfaction with the new apple; he wanted his original, and Alfonso has noticed how differently that portion has been interpreted over time.

A 1963 propaganda film produced by the United States Information Agency called “The Lost Apple,” about the exodus of Cuban children to the U.S. opens with a recording of the longer version.

Alfonso at the historic site marker for Camp Matecumbe, one of the temporary placement camps for Pedro Pans in Miami. Photo: Courtesy of Elisa Alfonso

Many who associate “Señora Santana” with Operation Pedro Pan see the “extra verse as a metaphor for the irreparable loss Pedro Pans experience and still feel decades later,” Alfonso said. In the film, however, the last verse “is paired with anti-communist messaging and a speech encouraging Cuban children to become, as historian Deborah Shnookal (2020) put it, ‘junior freedom fighters’ for a free (read ‘capitalist’) Cuba.”

Alfonso argues that, while the song later symbolized irreparable loss resulting from the Pedro Pans’ childhood exile, the 1963 film originally seems to present the lullaby as a motivator for viewers of the film to support a change in government in Cuba so children could recover “the lost apple.”

And while the operation is largely celebrated — perhaps in part due to crafted narratives like the one in “The Lost Apple” — it was neither easy nor comfortable for many of the Pedro Pans. It’s interdisciplinary research interests like Alfonso’s that help illuminate a more nuanced understanding of this complex time in our nation’s history.

Now, Alfonso is teaching in the University of Utah’s School of Music for her three-year fellowship, and she’s bringing with her a field of study new to the U: ethnomusicology.

“Of course, music cannot be fully understood if stripped from its cultural context, and so investigations into time, place, and people have long been part of the School of Music’s curriculum,” said Kimberly Councill, Director of the School of Music. “Alfonso’s specific focus and expertise in ethnomusicology, however, amplifies that inquiry to new and even deeper levels.”

Alfonso’s courses include an upper-level music history elective called U.S. Latinx Musicking which focused on the diasporic experience in the U.S. for Latinx people. In that course, she facilitated conversations around migration, diaspora, borders, and the liminality of intersectional identities in a sociohistorical context, including the way policy affects different groups from Latin America.

She is also teaching World Music Courses, which survey music of the indigenous peoples of Africa, China, Japan, Southeast Asia, Indonesia, and the Americas and explore the how music functions within these cultures with a look at the music, the musicians, their instruments, and the complexity of ideas, behaviors, and processes that are involved.

Like so many faculty members at the U, Alfonso’s unique history, passion, and care add dimension and texture to the tapestry of knowledge to be shared. Coupled with her interdisciplinary approach to scholarship and research-based practice Elisa Alfonso is an irreplaceable apple.