By Emeri Fetzer

Edith Carlquist Reed remembers the practice rooms at the University of Utah as the nicest she ever encountered in her life.

Better than those at Columbia University Teachers College, where she got her master’s in piano pedagogy. Better even than Juilliard’s practice rooms on Claremont Avenue in Manhattan, where students had to compete for time on pianos that were always kept under lock and key.

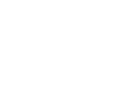

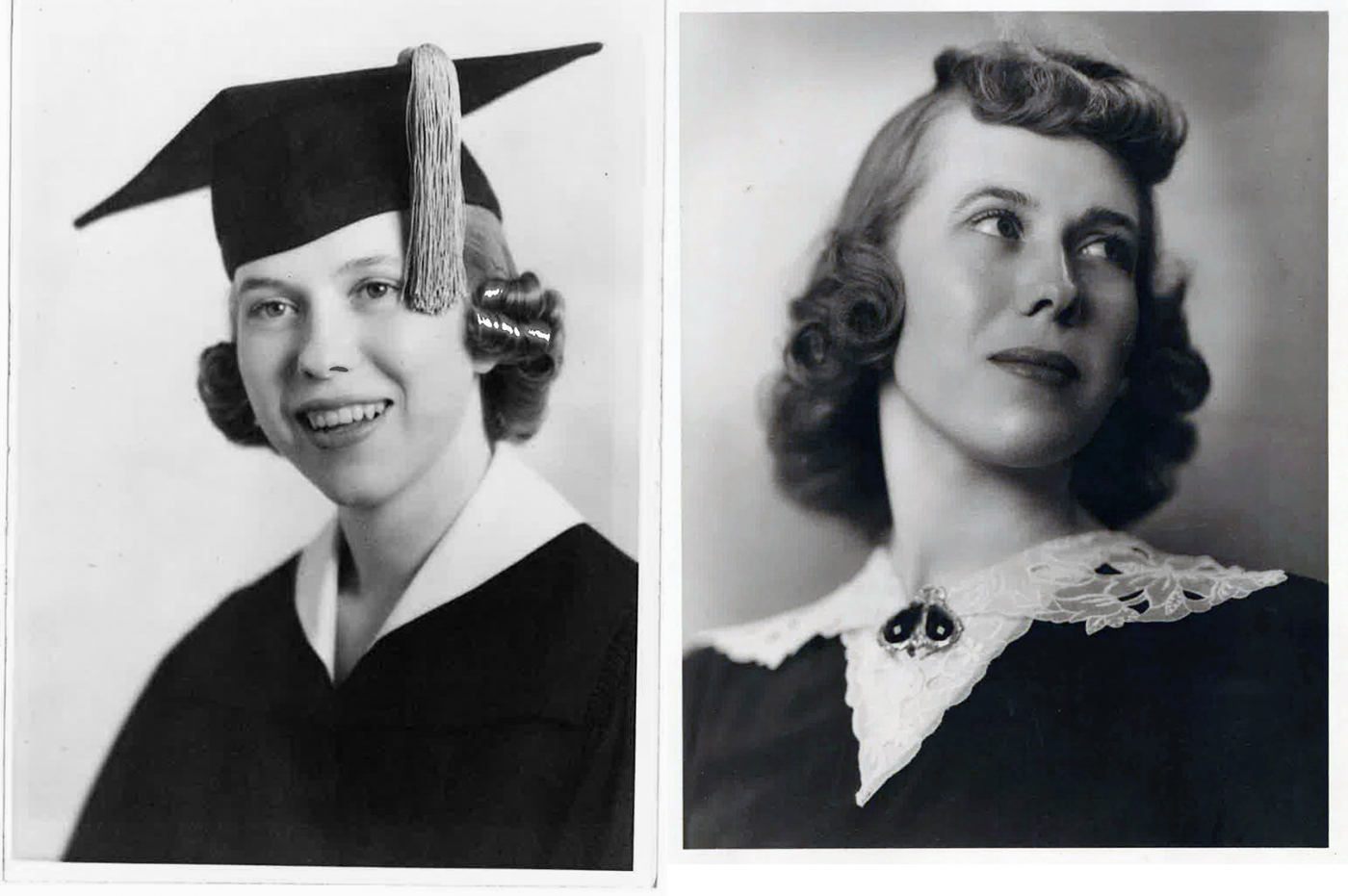

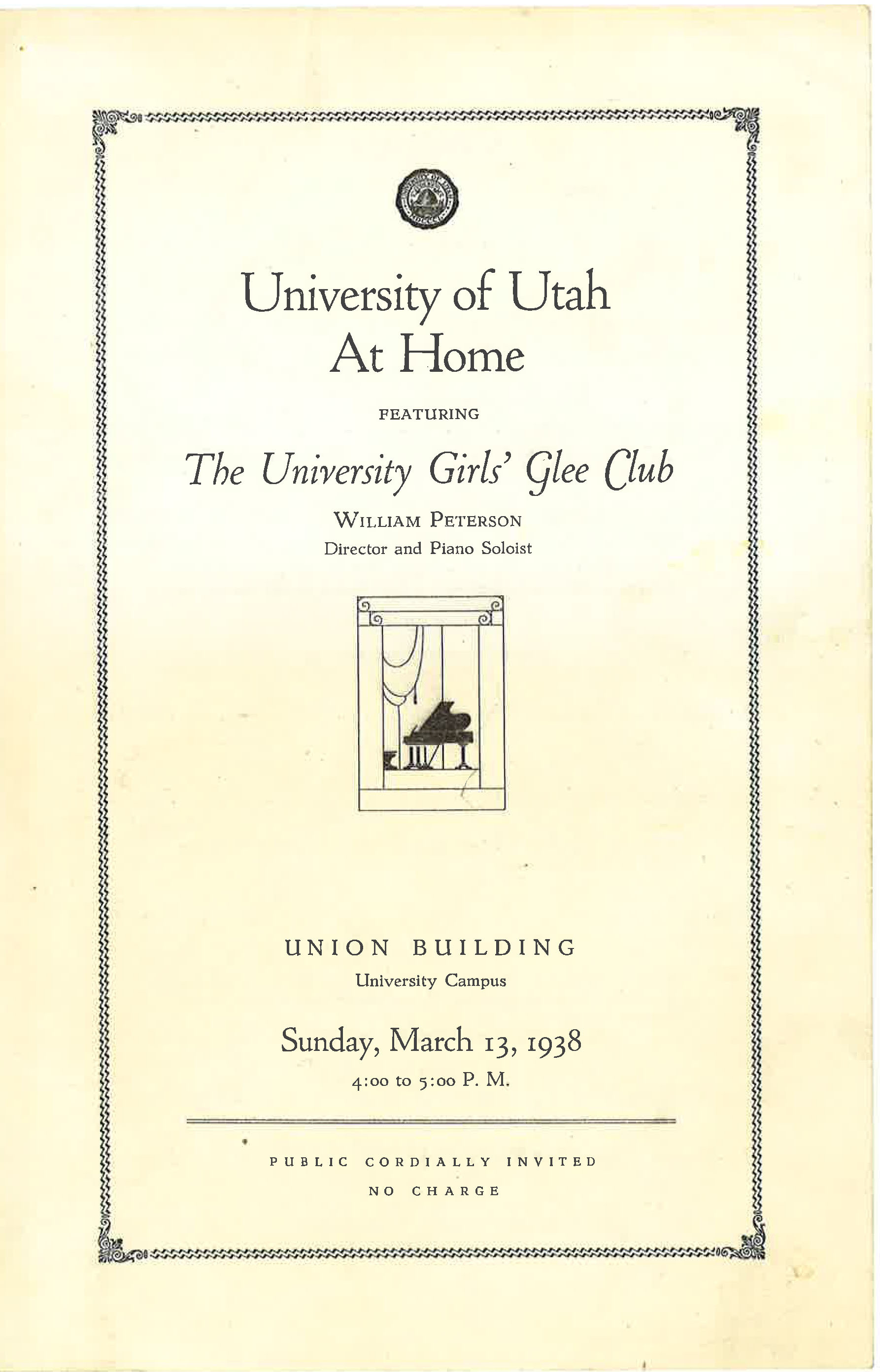

A bright blue-eyed co-ed with an insatiable love of music, Reed attended the U's Music Department with a partial scholarship of $25 per quarter. She maintained her scholarship throughout her studies, achieving high honors. In those days of a much smaller campus, all recitals were performed in the student Union building (Libby Gardner Hall before the Olpin Student Union was built), except operas, which took place in Kingsbury Hall. She remembers playing with the Girl’s Glee Club, performing marches at football half time, and looks back fondly on performing with her friend Ruth Hardy at the Baccalaureate celebration the night before commencement in the spring of 1938.

She had come a long way since studying piano with her aunt Agnes Dahlquist, whose home on Douglas Street was a lengthy journey from Reed’s family farm in Draper. From childhood through university, Reed would ride the streetcar (and sometimes roller skates!) from Sandy Junction to 200 South and wait for hours for her turn for a lesson. The freedom of those early years was perhaps the seed that later prompted her to go to New York City after graduation to continue pursuing piano, and specifically, piano education.

“I never had expectations of being a concert artist. My hands didn’t allow it — they were too small. I had no delusions of grandeur. It wasn’t my intention,” she explains. “But music has the power to change people’s lives like nothing else.”

So naturally, she followed her passion to Columbia University and Juilliard, then dedicated her life to cultivating young musicians, and sharing the power of music. One can hardly count the students who found a love of music under Reed’s tutelage since she began teaching in her rural Draper neighborhood at age 15.

Now a centenarian (that means she’s over 100 years-old!), she still holds weekly lessons for a handful of anxious learners, some of them her own great-grandchildren.

One student in particular inspires Reed with his consistent progress. A retired psychologist from Weber State University, Richard first approached her at age 75. “He said he had always wanted to learn piano. Now after ten years with me, you would be amazed at what he can do!” Reed gushes. Richard’s wife, a painter, was inspired by his artistic undertaking. Now they both travel from Odgen to Reed’s home for piano lessons.

Like most music teachers, the foundation of Reed’s philosophy is practice: “Every day,” she confirms! But her passionate guidance spans the practical to the profound.

“I honestly think there are probably 10 factors involved in getting the right finger on the right key at the right time, in the right manner,” she describes. “I have learned that if you are not speaking or singing along with it, you are missing the biggest thing. If I can teach them to sing, it comes out music.”

For Reed, learning to play an instrument is a bit like life, with all its hardships and triumphs.

“How do you eat an elephant?” she asks. “One bite at a time and chew, chew, chew — because it’s tough.” Most important to her is instilling confidence in her students. “Sometimes as a teacher, you can get a little impatient and want it to happen sooner,” she says. “But I always offer a prayer before I teach that I won’t say or do anything that will harm their regards for themselves.”

Reed’s daughter, Meredith Campbell, had many wonderful influences on her path to becoming a prominent professional violinist. But it was her mother who helped her become a musician. “She was the one who taught me to really play music — and to never give up,” Campbell said. “She practiced with me every day for an hour before school.” Every night in the Reed household, Edith would play piano in the parlor below her children's bedrooms until they fell asleep.

Of her incredible dedication to her children’s musical success, Reed simply admits that she wasn’t sure where music would take them, she just knew it would enrich their lives.

The Edith Carlquist Reed Scholarship in the School of Music offers further proof of her conviction. Benefitting University of Utah undergraduates pursuing piano with involvement in the Utah Federation of Music Clubs, the scholarship echoes the very assistance that drove Reed’s own success back when she was on campus.

The University of Utah remains a key chapter in a lifetime dedicated to the arts. A steadfast woman, whose grandmother walked the plains at 10 years old, and whose mother bought the Complete Works of Shakespeare with her very first paycheck, Edith Carlquist Reed upholds a legacy of strength and imagination. Just like her aunt Agnes’s, her home is filled with the work of Utah artists — not unlike the practice rooms that made a profound impact on her as a young student.

“It doesn’t matter what instrument you play, as long as you have music.” she affirms. “As King Benjamin said, ‘Use your heart that you may feel, use your ears that you may hear, and use your mind that you may understand the workings of the Kingdom of God.’”